Ebet Roberts on Photography, CBGBs, and Following Your Heart

Ebet Roberts is the visionary photographer whose lens has immortalized the pulse of modern music, from the raw energy of punk’s first wave to the timeless icons of rock, pop, and jazz.

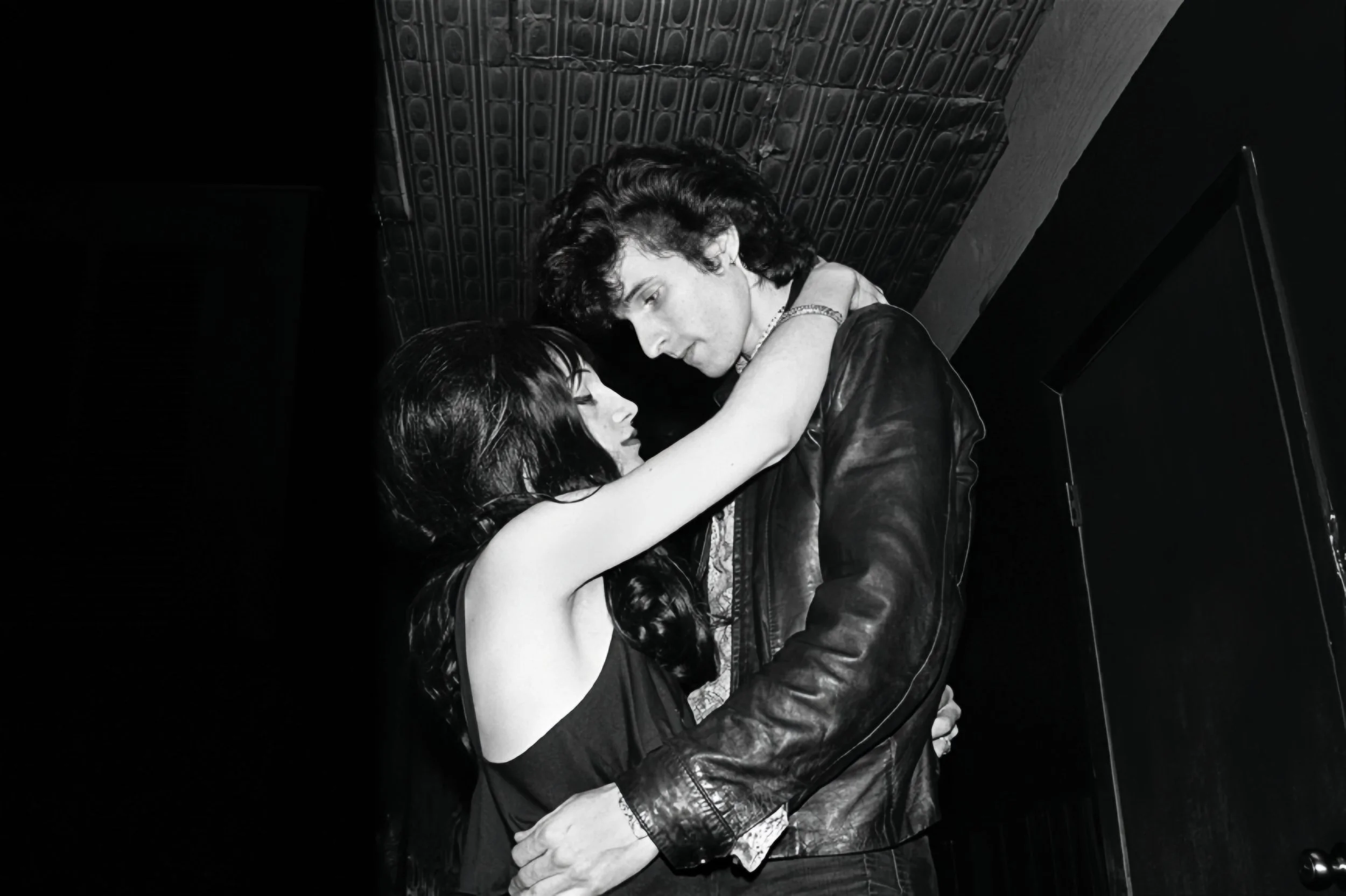

Born in Memphis and trained at the Memphis Academy of Art, Roberts moved to New York City in the late 1970s with a camera in hand and a painter’s eye. A chance gig photographing Mink DeVille led her into the dimly lit world of CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City, where she chronicled punk’s emergence in real time, freezing moments of rebellion and vulnerability that would define a generation.

Throughout her storied career, Roberts has carved an illustrious path documenting music’s most iconic figures including the likes of Bob Marley, David Bowie, Prince, Michael Jackson, Patti Smith, Aretha Franklin, and Miles Davis. Her iconic images have graced the pages of music tomes from Rolling Stone to SPIN, and her prints reside permanently in prestigious collections including the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, the Grammy Museum, and the Hard Rock Café. She has also been a key contributor to seminal books including Blank Generation Revisited, This Ain’t No Disco: The Story of CBGB, and Who Shot Rock & Roll: A Photographic History.

Over the course of four decades, Roberts has not only documented music history — she has shaped how generations see, feel, and remember its most electrifying moments through striking, unforgettable images.

KP: You initially moved from Memphis to New York City to paint, but switched to photography when you began documenting the scene at CBGBs. What was it that initially drew you to pursue photography over painting? Was it the visuals, the music, or both?

ER: I honestly did not decide to pursue photography over painting. I had gotten a camera to photograph my paintings with when I graduated from art school, but I was also beginning to take photographs just for me — mostly street photography. I was using some of the images as references for my paintings, which then kind of very gradually evolved into photo collage and manipulated photographs. At that point, I had done a lot of lithography at school, and I wanted to be able to combine my paintings and drawings with my photography. I applied to go to this workshop in North Carolina called Penland School of Craft — they had a strong graphics department. I went for a two-week workshop and ended up staying for four months. They just kept letting me stay, and the people teaching the workshops changed every three weeks.

After that, I got back to New York and was doing a lot more photography and getting more interested in it, and then a friend asked me to photograph his friend’s band, but I really wasn't interested in photographing music or even being a photographer, per se.

KP: Wow!

ER: Yeah, it was just a means for my art ventures. Well, I finally got talked into it, and his friend’s band, the Planets, were opening for Mink DeVille, who I didn't know anything about. But when I saw the bill, I absolutely wanted to photograph Willie [DeVille], the lead singer, and his wife. I talked to him after the show — we're talking unsigned bands at this point — he had given me his number and said that he’d love to take some photographs. At some point I called him after that and the band was playing at Max's Kansas City. He told me that I absolutely had to come down to take photos, and I told him that I really wanted to do something on the street. But he was insistent and told me to just bring my camera and take some backstage. I finally said okay because I thought maybe if I did that, then maybe I could do some more of what I actually wanted.

Anyway, after I photographed him backstage, someone came up to me saying that they worked for Capitol Records, that they just signed Mink DeVille that week, and that the photos seemed great — they wanted to see them. I literally stood there arguing, going, “I'm really not a photographer!” I told them that they were just a personal project for myself. Well, in the end, it took me quite a while to get them up to Capitol, but I did get some prints in to them.

At the same time, I had been waitressing to support my painting, and due to a new manager — who managed to fire everybody else that was working there — I had just lost my job at the same time that I had taken the photos up to Capitol. They loved them, licensed one, and started hiring me. I just sort of thought, well, my overhead is low, so if I could just do two or three jobs a month, maybe I could support myself without finding another job, right? So that's virtually what happened.

I still worked with Mink DeVille — they were playing CBGBs, and I went to photograph them there. The whole scene was just absolutely amazing, and I just immediately wanted to document it — not as a lifetime career, but just as a side project. So I just started. I don't think that I decided to be a photographer until after I was a photographer.

KP: Well, I love that. It was very serendipitous. It makes it much more magical that way anyway, right?

ER: It was magic. I mean, it was a ton of work. I was trying to keep up with everything. It didn’t come easily, but it’s not like I didn’t put any effort in, right?

KP: Of course! And your work eventually expanded beyond the New York punk scene. You went on to photograph some of the most iconic artists of all time, from Prince to Chuck Berry, Blondie to Bowie, James Brown to Bob Marley, and Whitney Houston to Kurt Cobain.

I always love to ask photographers this question, because there is always more than what meets the eye — do you have a favorite story behind one of the images that you’ve captured? If so, what is it?

“Rejection has to be a blip in the big picture.”

ER: I think one of my favorite stories is probably with — and you didn't even mention the artist — Miles Davis.

I had photographed Carlos Santana at a club in Midtown, and I was leaving at the end of the show when all of a sudden I saw Miles standing in the lobby. It was right when he started coming out of his recluse period, so I was just like, I have to get a photograph of him. He hadn't been seen in public forever.

So I kind of walked over and said, “I'd love to take a photograph.” He took off his glasses and just looked at me and smiled. He seemed to be pausing, so I took two or three photographs, and then as soon as I finished, he walked over and grabbed me by the waist of my jeans. And I went, oh my god, he didn't want to be photographed. He's mad. That was my initial reaction. I was just in a complete panic because I'm not very aggressive. But anyway, then he leaned over and said, “I want a photograph of me and my friend.” I said, “Oh, okay!” So he lets go of my pants and grabs my hand and starts dragging me all the way through this club. We were at the front door and had to go all the way to the back. I knew a lot of people there, and they kept whispering in my ear because he was in front of me, kind of dragging me — I had a camera in one hand and Miles in the other — and people were whispering to me, like, “Ebet, be careful, he's crazy.” I was just like, oh my gosh, what am I doing? So he gets to the back of the club and says something to security. The next thing I know, Carlos came down, and I took a couple of photos of him. I took them of both Carlos and Miles, and then Miles was like, “Oh, you’ve got to come over sometime and take more photos.” And I said, “Well, I'd love to, but not now.”

KP: Did you ever photograph him again after that?

ER: Yes! Well, I had an assistant there with me, so I finally told him that I did, and he said, “Okay, bring him!” So when he said that, I was like, oh, great. As long as somebody's with me, I'm fine.

And then, oh, I don't know, a year or two later, I got a call to photograph him for the cover of a magazine. I don't know if he ever remembered that night.

KP: That’s amazing. What a story.

You’ve also shared a story where you got to shoot Bob Dylan — who was one of your heroes — last minute after his manager asked you to do so in D.C. You frantically rushed there from New York and managed to make it in time, only to find out that Bob would “really hate these” because he “[hated] bright lighting,” which is quite astounding, since they asked you to photograph a daytime show! [Laughs]. Luckily, you had a second opportunity to photograph him the following week back in New York, and he loved the images.

I think this is a great lesson in staying both faithful to your work and also not allowing rejection to rattle you all that much.

What was that experience like, and what advice could you lend to women when it comes to facing rejection or failure?

ER: I think at the time I was meeting with his manager, and I was just completely let down. I really thought I had some great photos. It was just like, how could he not like them? And then this thought of, why did you call me to shoot this show if he doesn’t like bright lighting?

I don't think I felt as much rejection, because his manager also said that I could shoot him again. I photographed New York area shows, so I photographed them quite a few times during the next week. I mean, I've faced a lot of rejection, but I don't think at that point I felt that rejected.

But as far as rejection, I think you just have to keep doing it. It's really hard sometimes. I mean, when I was painting, I could never really promote my paintings — I just couldn’t do it. I'm still not the greatest at promotion. I don't know what the best advice is except for to keep going. Rejection has to be a blip in the big picture.

KP: Well, I think that's a great perspective to have. New York in the late 70s and early 80s was just filled with so much magic, it seems.

ER: It was.

KP: It was the intersection of everything progressive when it came to media, music, and the arts. Looking for someone to document the burgeoning scene at CBGBs, The Village Voice asked you to pick up the gig.

I’m sure you’ve been asked this a mind-numbing amount of times by now, but I simply can’t help but ask — is there any gig or any particular night that stands out to you the most while shooting CBGBs?

ER: I was shooting a lot at CBGBs, but it wasn't necessarily all for The Voice. They started calling me when I was already shooting there. I guess they would call the club looking for photographs of such and such band, and they got referred to me a number of times. I mostly started working with them that way — on things that I had already photographed. A lot of these bands, like Blondie and Talking Heads, were beginning to get a lot of press at that point, so there were a lot of different calls coming in, especially from The Village Voice.

And as for what stands out? My first assignment for The Voice was to photograph The Jam for the cover of the arts section. I think that was the first thing I did for them besides them using shots that I had already photographed. When I got there, and the club was just packed — you could barely get in the door. I finally got to the road manager and said, “Hi, I’m here to take photographs for The Voice,” which was supposed to happen before the show. And he said, “No, there's another photographer here shooting for The Voice.” And I said, “Well, I definitely have an assignment.” And he said, “Well, she says she does too.” Anyway, he finally was like, “I can't tell what's what.” So I was supposed to have maybe 10 minutes, but he decided to give us each five.

Anyway, it turned out that The Voice was irate at the whole thing, but they ran my photo.

KP: Well, it worked out then!

ER: Yeah, it's one of my favorite photographs.

KP: Really? How funny. That’s amazing then. It was meant to be.

Of speaking of modern photography, you said, “In a photo pit these days, you’re in with people using iPhones and point-and-shoot cameras. It used to be that you were with only professional photographers. Photography was art, and music was art, and they were interconnected. You could be creative. Now, the whole business is becoming so corporate.”

I imagine that you feel that much of the magic of photography has been lost to more modern methods and ideologies.

ER: I definitely do.

KP: I do, too! Do you think that we can ever regain the same enchantment that photography used to command, particularly in the world of live music? If so, how?

ER: I have no idea. I mean, music has become so corporate — it's just changed so much. I think in the 70s, it was all about the creative energy, and music, and art, and et cetera — which you said. I think maybe it started changing with MTV — they started wanting more control over image, wanting to own everything, and wanting to approve everything. It just became less fun.

I mean, it's really hard to be creative if you have an assignment and only have one song, two songs, or three songs to photograph an entire band. You can't sit around and wait for peak moments — you've just got to shoot like you're a machine or something.

I think the whole business has become completely corporate, which is not what I'm interested in. It’s really hard to get magical shots because you're just trying to get something on film for your assignment.

I think with Barbra Streisand, I had less than a minute. I mean, maybe 2 minutes, but not much more. It was crazy. I think there were three photographers shooting. I was shooting for The Times, and I had my own security guy, who said I could take photographs until she started singing. So she comes out on the back of the stage, holds up a mic, kind of looks at the audience, and smiles. Maybe she did a quick wave, but as soon as she picked up the mic, he went, “That's it!” He covered the lens. So sometimes it really is that short.

KP: Wow.

ER: I would have loved to have gotten some nice photographs, but I just have no desire to simply take photographs of somebody. I need to be satisfied artistically.

KP: I totally understand that.

How did being a woman in the music photography world affect your journey, if it did in any way? What advice would you lend to women who seek to get involved with photography?

ER: I've been asked that question so many times through the years, and I still don't have an answer. I think it definitely probably helped because I got quite a few calls over the years for saying an artist was difficult, and they thought I'd be great with them. There was this insinuation that because I was a woman, they would be better with me. But I also think I didn't get jobs because I was a woman — as far as going on the road or traveling, that kind of thing. So I don't know. I'm sure in the long run it wasn't a help — it was a hindrance. There weren't that many women photographers when I started.

KP: Right. You know, it’s funny. Every time I speak to a woman from the late 70s or early 80s New York punk scene, it's very interesting to me because they have such polarizing views of the same moment in time. Some women tell me that they felt super included in the scene, that they didn’t find their sex to be a deterrent, and others tell me it was a huge restraint.

ER: Interesting. That’s very interesting. I just have never known how to answer that question. I think it helped and it didn't help, but I think in the long run it probably didn't help.

KP: Yeah, I could definitely see that. What have you learned about people by photographing them?

ER: That one stumps me. I don't know what I've learned about people from photography except for the fact that I'm definitely trying to connect with them on a subconscious kind of level. I mean, especially during a performance — I'm just trying to capture a magical moment, which is something that I feel more than I think about. If I think about it, then it's too late. The moment is gone. So it's basically connecting with people — hopefully relaxing them and letting them know that I'm not a threat.

KP: Well, I think so many people get very on-guard when you put a camera up, so I think that's a very good natural skill for a photographer to have. I think a lot of people's insecurities come out. Cameras are scary — they've always scared me! [Laughs]. So it's great that you naturally just have that about you.

ER: I hate being photographed, so you'd think I'd have more sympathy. [Laughs].

KP: [Laughs]. It’s hard! What do you feel is something about your work that people tend to overlook? Is there an image of yours that’s a deep cut favorite, perhaps one that you felt should have been given more attention due to its background or subject?

ER: I definitely have photographs that I absolutely love that haven't gotten attention. But as long as I'm happy, that makes me happy. There are too many to name — many photographs of mine fall into that category. I'm always surprised by what gets a lot of attention.

KP: Really?

ER: Yeah, they’re not necessarily my favorite.

KP: That's so interesting. You know, it's funny, because when I talk to musicians, it's very much the same. A lot of artists will say that their favorite song off a record is the one that was the least listened to by their audience. I think as an artist, that happens a lot.

Apart from work, what advice would you lend to women about life in general?

ER: I mean, it's so whatever, but follow your heart. I basically got into photography by just wandering around in the art field. Just to go with the flow of what's happening. I think that's the most important thing for me.

KP: I think that’s great advice. What do you feel makes a provocative woman?

ER: Integrity.