Gaye Advert on The Adverts, Art, and Being a Pioneering Female in Punk

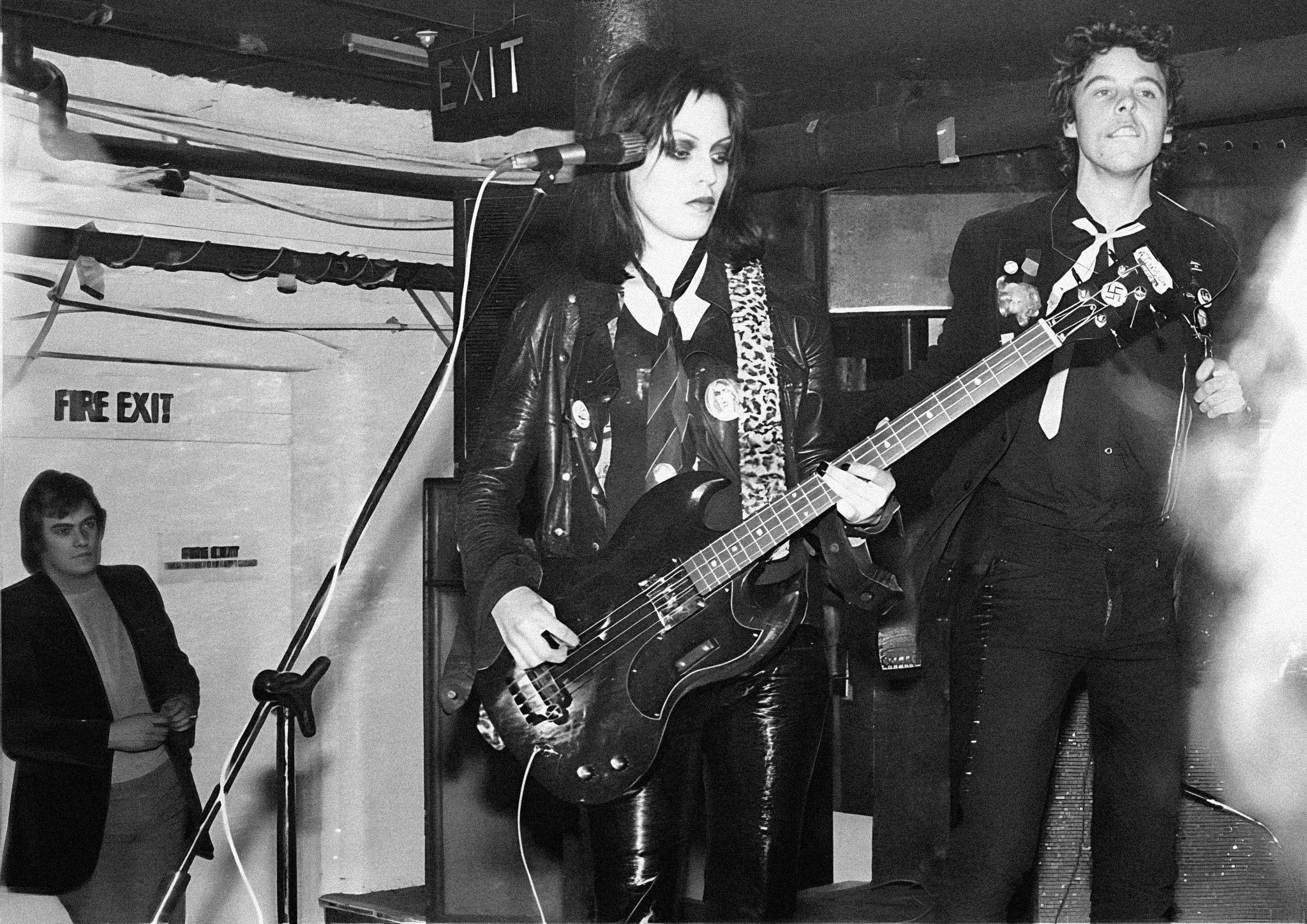

Often touted as the first female rock star of the punk movement, Gaye Black (Advert) stood as a kohl-rim eyed and jet-black haired beacon in a storm of chaos. Embodying fearless attitude and striking confidence, Gaye formed The Adverts alongside TV Smith in 1976.

After the duo relocated to London, they picked up guitarist Howard Pickup and drummer Laurie Driver, cementing the lineup that Gaye would provide the rhythmic backbone to in one of punk’s most seminal bands. Eventually forgoing the British punk scene after the dissolving of The Adverts in 1979, Gaye went on to pursue numerous other ventures, including the fine arts.

The echoes of her groundbreaking career continue to reverberate nearly fifty years later, remaining legendary as a woman who dared to defy, dared to disrupt, and dared to play punk rock, eternally changing the musical landscape for generations of women to come.

KP: What are you earliest memories of music or art? Your work across both fields is so distinct – is there anything you saw that perhaps may have influenced you in any meaningful way?

GB: Yeah, I've always been interested in sort of dark things, even since I was a small child. I love pictures of witches and wizards and skeletons and anything like that. I guess it’s just something that you're drawn to or not, isn't it really?

KP: Yeah, absolutely.

GB: I suppose my earliest memories of music – well, I mean, it was the music that my mother would listen to on the radio that I didn't like – but the first things I heard myself were possibly the theme tune to Fireball XL5 or Thunderbirds as well as The Beatles. I heard somebody singing a Beatles song when I was a little kid in the playground. I went, "What's that? I want it!"

KP: Which song was it?

GB: It was "She Loves You!"

KP: Ah, okay!

GB: But by the time my parents went to the record shop, it was "I Want to Hold Your Hand" just a few weeks later.

KP: That's amazing. What led you to initially want to explore a career in music? Was it something that was predetermined by you, or did it happen more organically?

GB: No, I was just drawn to music – whatever I liked that my ears flattered. That's the path I took, regardless of what it was – pop to start with The Beatles, and Monkees, and so on. And then sort of later on it went Alice Cooper and so forth.

KP: As prolific as you were as a woman in music, the press rather infamously tended to focus on your looks or criticize your musical ability, two things that don’t particularly plague men in rock bands in quite the same way. How did you feel receiving such harsh criticism or inappropriately-placed praise?

GB: Yeah, it was just really annoying because I didn't even think of myself as a woman in a band. I just thought of myself as the bass player, because I always sort of hung out with males I suppose and, you know, I really wasn't a girly girl or anything. It was horrible to have it constantly pointed out to me – not from within the punk scene, but externally, you know, within journalism and things like that.

KP: Yeah, I think that's very interesting. It kind of reminds me of how we don't want to be called "female" artists or "female" musicians, because, you know, for us, we just think of ourselves as musicians, right? You're just a bass player. You're not a "female" bass player, which very underhandedly connotes that "male" is the default.

GB: Yes, quite.

KP: So I think it definitely fits into that category. From what I understand, you weren’t aware that The Adverts’ debut single cover would appear in the way that it did, something that may have caused a rift within the band itself.

GB: Yeah, the way it came out, it was just a picture of me… I'm just the bass player on the cover.

KP: Yeah. [Laughs].

GB: And that was it. We were all angry.

KP: Unfortunately, though, we're decades later and women are still very often not in command of the way that they’re portrayed – those decisions are typically made for them by male executives. So what was your personal view on that situation? And looking back, do you wish it would have been handled differently? Or do you wish that something could have been done about it?

GB: Well, if it was up to me, I would have just designed the artwork myself. And I certainly wouldn't have been featured on it. But I mean, actually looking back, ironically, it turned out to be quite a successful cover.

KP: I mean, it's an amazing cover, I will say. [Laughs]. It's incredibly iconic.

GB: I sort of commandeered it myself indirectly, because there's a street artist called Pure Evil in London and when I first met him, he went, "I'm going to do a black metal version of you." So he did the one with the dripping eyes. And then I said, "Can I use that for my website or whatever?" And he said yes!

KP: [Laughs]. I know exactly what you're talking about. And it's really very cool. Given the era that you both fostered and were also present for, I just have to ask – what were some of your favorite nights out in that early London punk scene? Was there anything that sticks out to you that was especially memorable?

GB: Well, the gigs, of course. We'd go to see The Sex Pistols – we saw them quite a few times. And The Stranglers used to play regularly somewhere that was just a few miles away. We would always walk there because we didn't have any money. So yeah, The Sex Pistols and The Stranglers were probably the most regular bands that we would see, and also The Clash, The Damned... I can never name one particular gig because there were just so many. It was just such an amazing time of sensory overload, really.

KP: I can't even imagine having been present for that. How special. You’ve been quoted as saying that you became “disillusioned” with the British punk scene, which led to your departure from that world. I faced very similar feelings having left the fashion industry years ago. What were some of the aspects of that community that ultimately disenchanted you from it?

GB: Well, the journalists were getting into me, but I suppose also the band is kind of petered out – the guitarist just disappeared one day and never came back. And they sacked both drummers and we ended up with just me and TV Smith – the head of the band – and then this sort of semi-temporary drummer and guitarist. And by then he picked up Tim Cross as a keyboard player. And this was all that was left – and there was a bit of arguing going on within that. So I just thought, well that's it, I'll have a sort of break.

KP: And after departing from your career in music, you then began to pursue fine art. Was that always a focus that you had, even while performing? Or was that a pursuit that you cultivated thereafter?

GB: Well it wasn't strictly fine art, but I did a foundation year in art when I left school before the band, and then two more years in graphic design. One of the reasons for moving to London was to get a job designing, but of course, the band came along and that got shelved. But I had kind of gone back to art – stained glass actually – because my foundation year specialized in it.

KP: It's funny, because I just recently found out how stained glass is actually fabricated – it's extremely complicated and it seems like such a huge undertaking. There are just so many components. I was really blown away by it, to be honest.

GB: Yeah, yeah. It's a very laborious process. Which is why it's quite expensive to buy, obviously.

“Nobody wants to do things just to please everybody else and not themselves.”

KP: Who are some of your favorite artists, either visually or musically?

GB: For visual arts, Hieronymus Bosch, the female Surrealists like Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, all of those Second World War ones – well, quite a lot of them moved to the Americas, didn't they? Leonora went to Mexico to avoid the war. For contemporary artists as well, there's a lot. I quite like painting. I'm not so much into that sort of light-bulbs-turning-on-and-off thing.

KP: [Laughs].

GB: I like The Chapmans – they've done some wacky stuff. Painters like John Stark – he's very good. I generally go and look at painting exhibitions quite a few times a week. With photographic exhibitions, you can maybe see them online or in books better, but with painting, you really need to go and see it in person.

KP: There's such a craft behind them, texture, everything. I feel like should always see paintings in person, if you can. So I love all of your mixed media work – “Disruption” is one of my favorites. What is your process like? Do you employ any digital methods or is all of it done by hand?

GB: Yeah, I think that one was about in the middle – it was a photo of something that I did in the first place. But collage, I do a lot of collage. I like the crisp edges and the possibilities that come with it. And I like to mix it up with painting as well. Some of my most recent stuff, I've been painting abstract backgrounds with then this crisp sort of collage on top – I'm really pleased with the way it works out.

KP: It's all very beautiful. I was on your site the other day and it's really great work.

GB: I've got to update it, actually. I was busy making things for the Rebellion Festival all through July and August – I still have some of them that aren't on the website, well some of them sold, actually. But, in fact, we're going to create prints of the painted ones that got sold because they had come out really beautifully. We've got advanced technology to reprint them now and reproduce them – I'm quite happy about that.

KP: Yeah, that's amazing. As someone who broke tremendous barriers for women in culture, what advice would you lend to those who want to break into a male-dominated industry?

GB: I would say to try your best to ignore them.

KP: [Laughs].

GB: Just do what do what you want to do, what you feel you want to do, and at least then you'll be happy. You know, who cares about them? If you want to actually catch the mainstream, that's fine. But otherwise, nobody wants to do things just to please everybody else and not themselves.

KP: I love that advice. That's actually one of my favorite answers that we've ever gotten to that question – ignore them totally. [Laughs]. And so for our final namesake question – what do you feel makes a "provocative" woman?

GB: Someone who is not afraid to stand up for their own beliefs and nevermind anyone else, whether it's genuinely accepted or not. If you think you have to wear pajamas to the opera, then do it – well, people probably do, actually. [Laughs]. But anything, really. If it's your life's mission to rescue animals from the dissection laboratories, well then you’re one of the people that I respect most in the world. Nobody should be obliged to tell you not to because you've got your reasons, and they should always outweigh the downsides.

Photography (in order of appearance): Gems, Eric Waring, Ian Dickson