Kate Pierson on the B-52’s, Radical Eccentricity, and Reclaiming Your Power

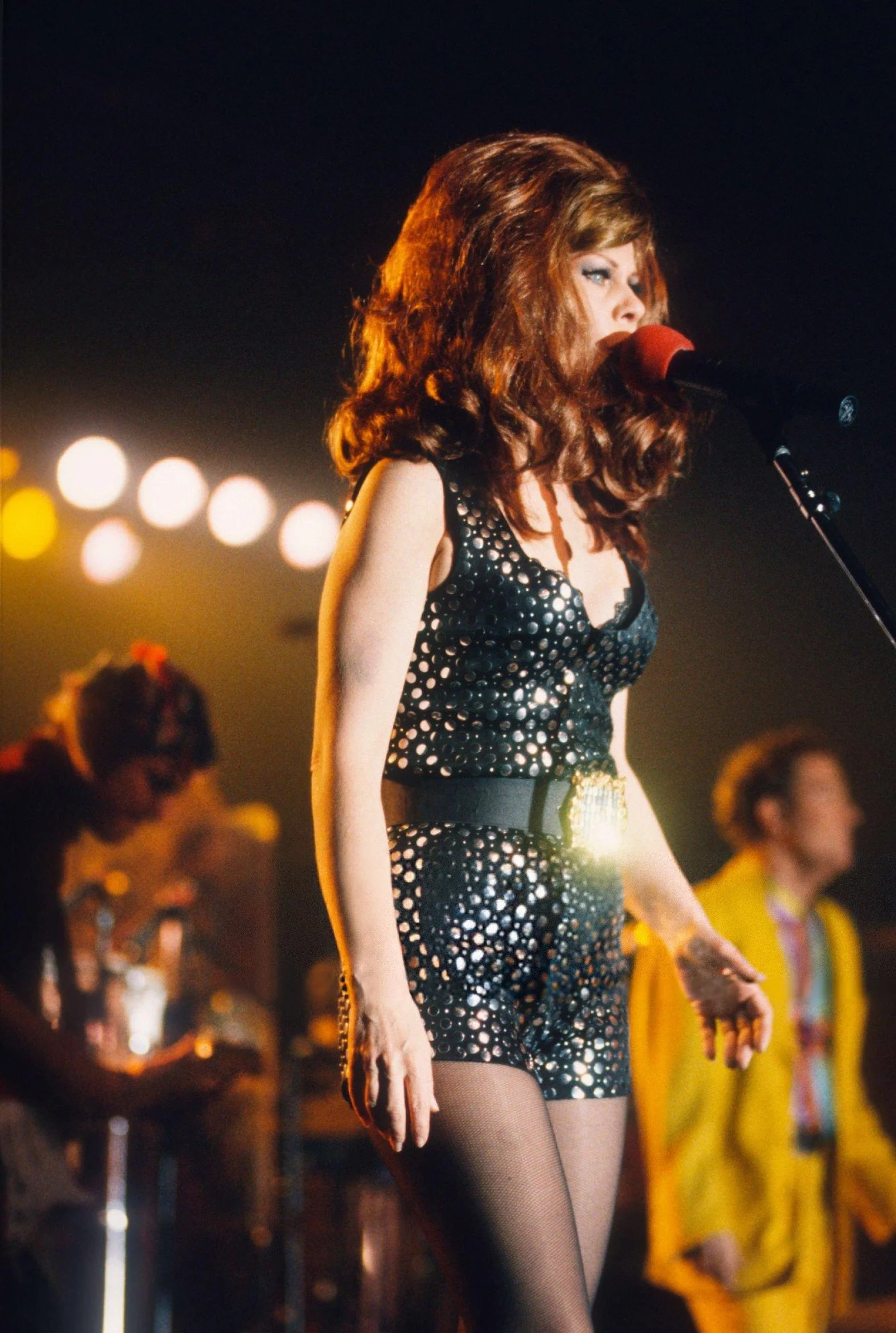

With her unmistakable beehive hair, cosmic style, and pivotal powerhouse voice, Kate Pierson has long been a beacon of unapologetic eccentricity in America’s post-punk renaissance.

Born in New Jersey and shaped by the bohemian spirit of Athens, Georgia, Pierson carved out a space for weirdness and joy in a male-dominated rock landscape, celebrating queerness, feminism, and individuality long before it was mainstream.

As a founding member of the B-52’s, she helped pioneer a genre-defying sound that blended punk, surf rock, new wave, and kitschy sci-fi flair into something entirely new, and entirely unforgettable. With her soaring harmonies, kaleidoscopic fashion, and magnetic stage presence, Pierson became an icon of unapologetic self-expression, inspiring generation after generation to embrace the joy of the weird and the liberating power of individuality.

Beyond the B-52’s, her collaborations with everyone from Debbie Harry to Iggy Pop and the Ramones reveal a chameleonic artist whose voice continues to resonate across generations. Now, Pierson is stepping into her own spotlight with a series of intimate solo shows — including an August 27th date at Blue Ocean Music Hall and another at Provincetown’s Town Hall on August 29th — before embarking on a highly-anticipated Devo tour with the B-52’s.

With a legacy as vibrant and fearless as her signature style, Pierson remains an enduring trailblazer — and living proof that being boldly yourself is the most radical act of all.

K: As a native New Yorker, I’m always curious about how growing up in the Tri-State Area has influenced someone’s path, either personally or creatively.

What was your earliest exposure to music growing up in New Jersey, and how do you think it helped shape your artistic sensibility?

KP: Well, I grew up — initially, for the first eight years of my life — in Weehawken, New Jersey. My father was a professional musician when he was in his early twenties. He was in a big band and played guitar. He played guitar his entire life, and I grew up with him playing all the time. He had to quit playing professionally when he got married, but he never stopped playing at home. He also had a huge record collection — playing records was a big deal for him. So I grew up hearing jazz and big band music.

K: I love!

KP: Yeah! He also collected that sort of trendy '50s stuff — loungy music… Kai Winding, Doris Day, Ella Fitzgerald, Yma Sumac, all of those great singers. I heard a lot of popular music growing up. I was also exposed to many kinds of eclectic music. And also, on TV — I mean, I’m really dating myself here — but, you know, there was The Ed Sullivan Show. There were some good music shows on TV at the time, even though the Top 10 hits were kind of awful. I remember that my very earliest memories were of hearing some really stupid music. One of the hits was “Que Sera, Sera” or something like that. Which is a good song, but you know what I mean — they were really white bread, sort of mainstream hits.

Then, one day, I heard “Great Balls of Fire” by Jerry Lee Lewis blaring out of this old radio console that we had — one of those big wooden ones. And I just had a fit. I remember laughing and rolling on the living room floor. It totally blew my mind. From then on, I was a rock and roll fan. I also remember Elvis coming on The Ed Sullivan Show. We watched it as a family, and I was like, “Whoa.”

Also, my grandmother played the piano and sang. We lived in her house, so there was music all the time. My brother played the clarinet, and I took piano lessons. There was just always music all around me.

Growing up in the Tri-State Area certainly impacted me. Later on we moved to Rutherford, New Jersey, which was just a bus ride from the city. My friend, Gretchen, and I would hang out in Greenwich Village quite a bit. We heard folk singers, and we were definitely affected by that scene. Even though we couldn't go see a lot of big concerts — our parents weren’t going to let us go into the city alone at night — my father did take me to some folk concerts, I think at Palisades Park. I saw Buffy Sainte-Marie, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Mississippi John Hurt… I got to hear all of these folk icons. So I was very informed by the folk movement, which was also happening in Greenwich Village at the time.

K: Right! I mean, I’m from New York — I was born in Brooklyn — but it just seems, especially back then, the city was so formative. It must have been incredibly inspiring.

KP: Yeah, yeah. Even though I was in the suburbs, I was definitely still very affected. I got Broadside Magazine, and I was able to go into — I think it was Gerde's Folk City. I went there, and I often wonder, why didn’t I just, after high school, run away to the Village and start singing with my guitar?

But I took a different path… which ended up —

K: …Working out anyway, right? [Laughs].

KP: Yeah, it worked out anyway. [Laughs].

K: Well, speaking of your other path that really worked out… [Laughs]. For those who aren’t aware, can you recount the story of the fateful night at a Chinese restaurant that led to the formation of the B-52’s?

KP: We couldn’t afford food, so we went to this Chinese restaurant, but we really couldn’t afford the food there either! [Laughs]. So we got a Flaming Volcano. It had six straws and was one of those tiki drinks with a little flame in the middle — rum-based, probably — and we all shared it.

Then we went over to our friend Owen Scott’s house — he was with us that night; he was the sixth straw. So we went down to his basement. He’s a clinical psychologist now, but at the time he was in college and also a musician, so he had all of these instruments down there. He went upstairs to write a paper, but we stayed down there jamming. That’s when we came up with a song called “Killer Bees.” We never released it, but it had a chorus that went, “Buzz, buzz, buzz, buzz, buzz.” Fred was kind of obsessed with this idea that killer bees were coming up from South America and invading the US, so it was based on that concept. I still hope that we’ll finish that song someday.

K: You should!

KP: I really hope so, too. But we started jamming that night, and I guess that set the template for how we wrote songs from then on — we always wrote by jamming. Rick and Keith were just playing whatever — guitar and bongos, I think — and the rest of us, Cindy and Fred, just started wailing and coming up with stuff. That’s how we always wrote. I always say that we sort of started by spontaneous combustion. There was no plan. No one ever said, “Hey, let’s start a band,” although all of us had dabbled in music somehow. Keith and Ricky had done some stuff together, Fred recited poetry with Keith playing music, Cindy sang with Ricky, I was in a folk protest band in high school, and I had also done a couple of things with Owen — the aforementioned Owen Scott.

So that night set a kind of template out for us. It just so happened that I played bass keyboard, and I play guitar, too, so I played guitar on a couple of songs. We all sang, Keith played the drums, and Ricky played the guitar.

We even had a few things recorded on a reel-to-reel tape recorder for some of our first performances. I guess we didn’t have a full set of instruments or a drum kit, so we used tapes — it was kind of our version of overdubbing. I remember we played “Devil in My Car,” and something always happened during that song, like the tape recorder would get unplugged or something.

But that’s generally how we got started. Then we decided, “Okay, let’s convene again.” We started writing together, meeting regularly, and eventually we got a little studio. Then we got a little more serious about it.

Someone suggested that we go to New York City with a tape, so we did. And then we started going often because there was no scene in Athens — there was no real place to play. Our first show was at a house party on Valentine’s Day in 1976 or 1977.

“I think that all of us felt like outsiders — but together, we were insiders.”

K: That’s amazing. And the name, right? I was reading that you were named after a beehive hairstyle.

KP: Yes! Keith Strickland came up with the name. He had a kind of waking dream where there were all of these women all playing keyboards with bouffant hairdos, and someone whispered to him, “That’s the B-52s.” That was a slang term for beehive hairdos back then, because they looked kind of like a nose cone.

K: I get it! And speaking of the band, I think that you and Cindy have some of the greatest harmonies that any duo has ever had in the history of music, and I’m sure many rock historians would agree with me on that undoubtedly. [Laughs]. How did the two of you develop such seamless vocal chemistry?

KP: Our harmonies were definitely based on jamming. Sometimes we would just stumble onto these harmonies during a jam. We’d record it — at first on a reel-to-reel tape — but then we got a double cassette deck, and we’d make edits on the second cassette. We’d pick out parts from the jam, and that’s how we’ve always written, with some exceptions — collaging the parts together.

So even if I sang the high part and Cindy sang the low part, it was just something that happened during the jam. Sometimes we’d even cross over. But then we’d try to replicate it exactly and do it live the same way that we did in the original jam.

It gave the harmonies a really unusual, spontaneous quality. We never sat down and said, “Let’s do this interval” or “Let’s sing a third or a fourth.” It just happened very organically.

K: Yeah. I mean, it genuinely sounds like magic, so it’s really cool to hear that it actually was that natural, too.

KP: Yeah, yeah. I mean, it’s just lucky that our voices complemented each other in such a way that they did.

K: On the topic of you and Cindy, you both collaborated with the Ramones and Debbie Harry on “Chop Suey.” In speaking of relocating from Athens, Georgia, to New York City for it, you said, “When we got to this scene in New York, first they said Cindy and I were drag queens, then they said, ‘They’re probably English,’ and then they thought, ‘They’re from Mars.’ It was a shock, but we got people dancing.”

I’ve always felt that you’ve somewhat defied both expectations and standards in whatever scene you’ve been in. The B-52’s in general could be categorized as a band that was too party for punk, and too punk for commercial — your post-punk compositions hold themselves heavily, and I feel they’re some of the best in the genre.

How did these reactions shape your sense of self, as either a woman or a performer? Did you ever consciously feel like an outsider regardless of where you went?

KP: Well, I think that all of us felt like outsiders — but together, we were insiders.

Athens was definitely a breeding ground for that. You know, the South is known for accepting eccentrics, and Athens was full of them. The first person Fred met in Athens was this guy Ort, who had a record store, Ort’s Oldies. It was just full of people like that, who would always tell you a long story.

Athens was this perfect place where you could be an outsider — and that was fine. You could be as “outside” as you wanted. You could be gay, straight, or in between. Keith Strickland always said that he never felt like he had to come out in Athens, because he was just accepted. Everyone was accepted for who they were.

Even though it was a college town, it didn’t really feel like one when we started. It was still very divided between the university and the old farmer’s town — there was a feed store, a seed store, things like that.

But I think when we first went to New York City, we weren’t really ready for the way that people perceived us. Our friends accepted us completely. We had this larger circle of truly eccentric, fun people who loved to dance — and we wanted to be a dance band because everyone loved to dance. We went to parties — we’d crash house parties in Athens, and everyone was dancing.

So we went to New York — to the punk clubs — and nobody was dancing. Everyone was leaning against the wall in their cool leather jackets, but when we hit the stage, our friends — who had come with us from Athens — started dancing. And then everyone started dancing with them. Even the coolest people in the club, the ones leaning against the walls — they did, too. We started something.

That’s why people said, “Wow, they’re so weird.” That’s why people thought that we were from England or asked, “Where are they from?” Because how could a band like this be from Athens, Georgia — a place that no one had even heard of?

People thought that we were so new and different. Even with our first Saturday Night Live performance, everyone said, “Oh my God, they’re so weird. Where did they come from?” And it always astonishes me that people saw us that way — as that weird or different or startling — because, to me, we were just doing our thing.

It wasn’t planned. Our look wasn’t planned. It was just us grabbing stuff from a thrift store, trying on silly wigs — not to be glamorous, but just to be fun. It felt so natural to me. But people looked at us like, “What is that?”

K: And I guess you always had this innate sense of confidence, but is there any advice that you would lend to women whose mere existences tend to defy the norm as well?

KP: Well, I would never say that we felt confident. Part of the whole wearing wigs and dressing in thrift store clothes — that was, for all of us, something to disguise our fear. You know, once you put a wig on, anything goes. You can be anyone, do anything.

We were terrified when we first got on stage. When we did Saturday Night Live, we were like, “Oh, holy shit, we’re on live TV.” But we pulled it off. You could kind of see it in our robotic movements — that was just fear. I remember it so clearly.

But as for advice, I would say to embrace who you are. Just don’t listen to the noise. Especially during your formative years, when a lot of people might be telling you how to be. And now, with social media? The pressure on young women? I just can’t even believe it. There’s so much pressure to be a certain way, to live up to these curated versions of life.

Even watching TV shows now, there’s a lot more diversity and acceptance of different sexual identities and values. I think there’s more openness among young people than there was in older generations. But at the same time, there’s this huge political pressure on women. Women’s rights are being taken away by the second. It’s horrifying to think that we’ve been thrown backwards — back to when I was young and abortion was illegal. My college roommate almost died from a backstreet abortion. She says that I saved her life by going to get the nurse who lived upstairs. I mean, it’s horrifying to think that things have regressed to that point again.

So I guess what I would say to young women is to fight for your rights.

“I think we had the impact that we did because we were queer, we were different, we were accepting, and our message was all about acceptance. It was fully about being yourself.”

K: Definitely. It’s unfortunate that we even have to, but especially in this country right now, it’s dire.

KP: Absolutely. So be who you are. Fight for your rights. And don’t take any wooden nickels from fools. Stay away from the fools, because love rules. Just keep love in your heart and always have a ton of compassion.

K: Your cultural impact — particularly on the queer community — is profound. Looking back, what do you think made the B-52’s resonate so strongly with queer audiences and misfits around the world?

KP: Well, most of our band is queer. And, like I said, they didn’t even feel like they had to come out. Fred is — you know — very gay. Let’s just say Fred is very out, very flamboyant. Keith and Ricky? You wouldn’t necessarily label them in any specific way. It wasn’t about identifying. It was just that we were so much ourselves — each in our own personas — so different and so eccentric.

I think the Athens effect really seeped into us. That kind of accepting eccentricity — it’s part of the South, you know? Even though there’s a lot of prejudice down there, there’s also this strange acceptance of eccentricity.

So, I don’t know. I think we had the impact that we did because we were queer, we were different, we were accepting, and our message was all about acceptance. It was fully about being yourself. Like it says in “Love Shack”: “Stay away, fools, 'cause love rules at the love shack.” And it’s true.

Fred has a line in “Moon in the Sky” that goes, “If you're in outer space, don't feel out of place, cause there are thousands of others like you.” And I just think that kind of sums it up. Some of our lyrics really say it — we are all about acceptance, about embracing differences.

Let your inner eccentric fly.

K: Speaking of “Love Shack,” I wondered what it meant to you that “Love Shack” became such a massive pop culture staple after a decade of underground success. I feel like so many people wrap your discography up in these supernova party tracks, but there is so much more to your storied catalog.

How did that shift from the underground with this very driven, post-punk sound to blockbuster success make you feel, both personally and professionally?

KP: Well, it was a surprise to us that we had this comeback after Ricky passed away, because we thought the band was going to end in a lot of ways after his death. But we came back together again as a healing process, and we realized what a precious thing we had with each other. We decided to write just for ourselves. We even said out loud that we weren’t doing this to be a hit. This was just for us.

It just turned out that “Love Shack” was such a hit, and “Rome” was also a huge hit. I think we potentially had some other great hits as well on other records. “Summer of Love” on Bouncing Off the Satellite — which was the last record that Ricky worked on — the record company totally dropped it because they thought that was it for them. They were just not going to push that record. “Summer of Love” was racing up the dance charts, but nobody really worked it. So I think we were sort of on our way to a little bit more of a mainstream kind of sound at that point.

But with Cosmic Thing, we added the bigger band. We just completely changed our sound. So I think its success had a lot to do with being less sparse and punky sounding — it was definitely more 80s, more in tune with what was going on at the time. Everyone from the punk movement, from the Talking Heads to Blondie, evolved into different sounds because you’ve got to keep changing. But it wasn't a conscious effort.

“Love Shack” itself just came out of this jam, and it had different iterations, but the final product was bingo.

K: Well, it’s such an iconic track, as were all of your looks. Your personal visual style — bright wigs, vintage dresses, and kitsch glam — became iconic. Was there a deliberate fashion philosophy behind any of it?

KP: We just decided that we would mine the thrift stores. We weren’t really conscious of trying to be in vogue with what was happening in the punk movement, but the punk movement definitely was inspiring — especially the idea of creating your own fashion. I mean, Debbie Harry famously wore a garbage bag and bright neon colors, so there was that spirit. But I think this kind of thrift-store chic was happening in small towns across America. It was this growing, scrappy kind of creativity.

We just aimed to get the craziest things. We’d find the brightest, most outrageous outfits. Cindy had this one dress that was a semicircle, kind of like a jumper, and when she opened her arms, it formed a full semicircle. It was a watermelon. [Laughs]. And I had a bright orange dress made of lurex, with leeks all over it. We wore wigs, too. But, as I’ve said, it wasn’t about being glamorous.

We did, however, draw a lot of inspiration from Fellini films. During that time, it felt like everyone around me was watching independent movies — Fellini, Antonioni, all the arthouse directors. We were especially inspired by Fellini’s use of exaggerated, surreal femininity — this blown-out, mythic idea of women.

And also, as one critic put it, our style had this “American trash” aesthetic. We loved kitsch. We loved finding stuff in thrift stores that just made us laugh. It all came very naturally.

Later on, we worked with friends who designed clothes for us. Cindy and I would draw designs and have them made — these outlandish, spacey-looking things with big collars. Just crazy, fun outfits.

Then later, on tour for Cosmic Thing and Good Stuff, I had Todd Oldham design my stage outfits, and that was fabulous. These days, I still work with a designer friend who makes my stage clothes, so not much has changed!

K: Yeah, and you guys sound incredible! I was watching a clip on YouTube last night — I think from a year or two ago — and it’s amazing. You really do sound exactly the same.

KP: Thank you! I still think we have the sound. I really do. And we have a great band — Tracy Wormworth and Sterling Campbell have been playing with us since Cosmic Thing. Ken Maiuri joined, and Jon Anderson plays guitar now that Keith has retired from touring. We’ve got a kick-ass band.

K: You really do. I mean, one of the most common complaints about bands over the decades is that they lose their sound — and that’s expected! You don’t expect people to sound exactly the same over time. But my God, you guys sound… I swear, exactly the same. It’s crazy. It’s such a gift.

KP: Thank you so much! That means a lot.

K: Moving onto your solo work, creation is such an endless journey of self-discovery. What did you learn about yourself as an artist while working on 2015’s Guitars and Microphones, your debut solo album?

KP: Well, I realized that I could collaborate with anyone — even before that moment — because I did a project in Japan in 1999 called NiNa.

We were on a bit of a lull with the B-52s at the time, and I had already written a solo record. I had all of the songs together, but our manager back then really didn’t want anyone diverging from the band. He told me that I couldn’t put it out because I was under contract with Warner Brothers. It was, “Oh, wait on this,” or “Why don’t you write a book instead?” He basically suppressed that record.

There’s actually one song from that period, “Always Till Now,” that ended up on Radios & Rainbows, my new record. So that one did survive from those early solo sessions.

But NiNa — that project in Japan — was kind of a revelation. It was with members of the Plastics, who were sort of like a Japanese counterpart to the B-52s. One of them had become a huge producer and invited me over to collaborate with him and another former member of the Plastics. It became a big hit in Japan — on Sony — and we even toured. It was such an interesting experience. I realized then that I could write and collaborate with people who didn’t even speak the same language. I worked with Yuki from Judy and Mary, and we wrote lyrics together through a translator. It was so fun. That really opened up a creative wellspring in me.

Later, I met Sia, and my wife, Monica, suggested to her that I still wanted to make a solo record. I had wanted to do that my whole life. Sia really helped me. We went on a few writing sessions with people that she had collaborated with, but then her own career started blowing up, so I started going on my own — and it just worked. Every time. It was like magic: even if I didn’t know the person, musically we could just connect and create something.

That was so empowering. It felt so good to be able to express things that I couldn’t necessarily express with the B-52s — things that were more personal. Some songs were like stories; others just expressed something deeply meaningful to me.

K: It’s so incredible that you could find that. And you mentioned your wife, Monica Coleman, whom you married back in 2015. Your story is so, so sweet. I’m gay myself, and it can be a bit of a tightrope walk within a career to be so open about who you truly are. Did you have any hesitation about going public with your love, and what is the greatest thing that she has taught you?

“Let your inner eccentric fly.”

KP: Well, I really had no hesitation. Before her, I had been with men, but it just felt so natural when I met her and we got together. It was like, “Wow.”

I mean, yes, there is a difference being with a woman, for sure. But at the same time, it’s still a relationship. It didn’t feel to me like I had to sing it from the rooftops: “I’m gay now!” [Laughs]. I guess I am bisexual, but no one ever really asks or talks about that much.

I just saw Margaret Cho recently here in Provincetown, and she was saying how she’s been with men and women — I related to that. What’s most important to me is that I feel safe. I live in Woodstock, New York, and part of the time in Truro, near Provincetown, so this is gay central. I definitely feel that we could hold hands here.

But I’ve honestly never really felt like we couldn’t do that. I’ve never been in a place where I thought that we couldn’t be affectionate. But, then again, we haven’t really traveled together to the Middle East or anything like that. That might be more difficult.

K: Definitely.

KP: But yeah, it’s getting scarier even here lately with all of the horrible things happening to the trans community. Just when things were opening up and becoming more accepting, now there are these movements — especially from governments — that are trying to shut down the very spaces and programs that foster acceptance, love, community, and empowerment for the LGBTQ+ community.

So it’s really important to me to be active and do what I can. We just had the second-ever Pride here in Woodstock, and being a part of that — right in my own community — felt so good. Just marching in the parade and showing up.

And as for what Monica has taught me? She has totally empowered me. The relationship that I was in before her was emotionally abusive. I wrote a song about that called “Higher Place.” It’s really about my relationship with Monica and that transition from something abusive to something empowering. It's about women finding their power. There’s a line in it: “We only got here walking on other women’s bones.” And that just sums up so much of what I feel.

The women’s movement has been incredibly empowering overall, but Monica, in particular, has empowered me personally in so many ways. She really made me feel like I could take control — especially with the business side of things.

We ended up switching our financial team. Before that, we were still using the team that had worked with the B-52s, and I think a lot of bands have this irrational fear that their manager is like their dad or their financial advisor is like their overlord. But she helped me see it differently — we’re hiring them. That was such a wake-up call. It made me realize that we do have power over our finances and our destiny. And that was a huge shift for me.

She’s just one of those people who can do everything. She’s a potter, she makes jewelry, she can fix anything. She always wants to do everything herself. She taught herself to knit and opened a wool company here in Woodstock. She’s even done overseas construction projects. It’s kind of incredible.

K: Wow! She’s a Swiss army knife! [Laughs].

KP: She really is. And she really did empower me to be more assertive — especially in business, which is not something that I’ve ever been comfortable with. Like a lot of musicians, that’s my weak point. We signed bad deals early on, and if you watch that Billy Joel documentary, your hair will stand on end — it happens to even the smartest, most talented people.

So yeah, Monica really made me aware of all of that. It was a wake-up call to take charge — not just of your business affairs, but of your life.

K: I’m so happy that you could find that. You guys seem amazing together.

Looking back, what would you tell your younger self?

KP: Oh, don’t go with that abusive boyfriend! Only you can see that.

But do you know what it taught me, being with that guy? I understand now why people always say, “Why didn’t she just leave?” I get it. I really do. And I don’t know if you can explain that to someone in a way that they’ll actually understand without them having gone through it themselves. I hadn’t gone through something like that before, but being in it gave me a whole new understanding.

If I could talk to my younger self, though — honestly, I’d say to do what I eventually did. I used to just let things happen to me. I think when you’re young, there’s this sense of, I just want experiences. I’ll let life happen to me. But what I’d say now is to not just float through. Seek mentors. Seek people who are good — who lift you up. Don’t let these other people — the ones who just want to suck your energy — into your life. Try to find people who can actually teach you something, and follow their lead.

K: What advice would you lend women about life, work, or love?

KP: Be open. And when I said earlier to seek out mentors or people who can guide you, I didn’t mean don’t be open — I just meant to be intentional about who you let in.

I do believe in being open to new experiences. I would definitely advise any young woman to explore — go to Europe, travel a bit. Try to build that into your college experience if you can. Study abroad, go somewhere new, maybe South America, learn a different language. Open yourself up to other ways of living.

And when it comes to love, I’d offer the same kind of advice: don’t just let things happen to you. Don’t fall into something just because it’s there. That’s how people can end up in bad relationships — just because that one person is around.

Try to be intentional. Seek out people who elevate you, who make you feel good about yourself. Surround yourself with people who bring out your best.

K: What do you feel makes a provocative woman?

KP: A provocative woman is someone who speaks her mind.

Don’t be afraid to speak out. So many women are still timid — I know I was, especially in early college. I was part of SDS and other political groups, protesting the Vietnam War, and trying to support the civil rights movement. But the men were always the ones speaking. They’d fight to grab the microphone, to dominate the space. I think that women really have to learn to speak — to claim that space. Like Kamala Harris said, “I’m speaking.” You get interrupted a lot as a woman, and you have to push through that.

I think what makes a woman provocative is the courage to raise her voice without fear. To speak up for what she believes in, to get involved, to take action. Whether that’s activism, art, politics, or just participating in your local community — do it with passion, and use your voice.

And even just joining with other women, being part of something larger — that’s powerful. There’s real strength in numbers.

But above all: don’t follow leaders blindly. Always speak for yourself.

Photography (in order of appearance): Josef Jasso, Janette Beckman, Gie Knaeps, Clayton Call