Leah Shapiro on Rhythm, Recovery, and Black Rebel Motorcycle Club

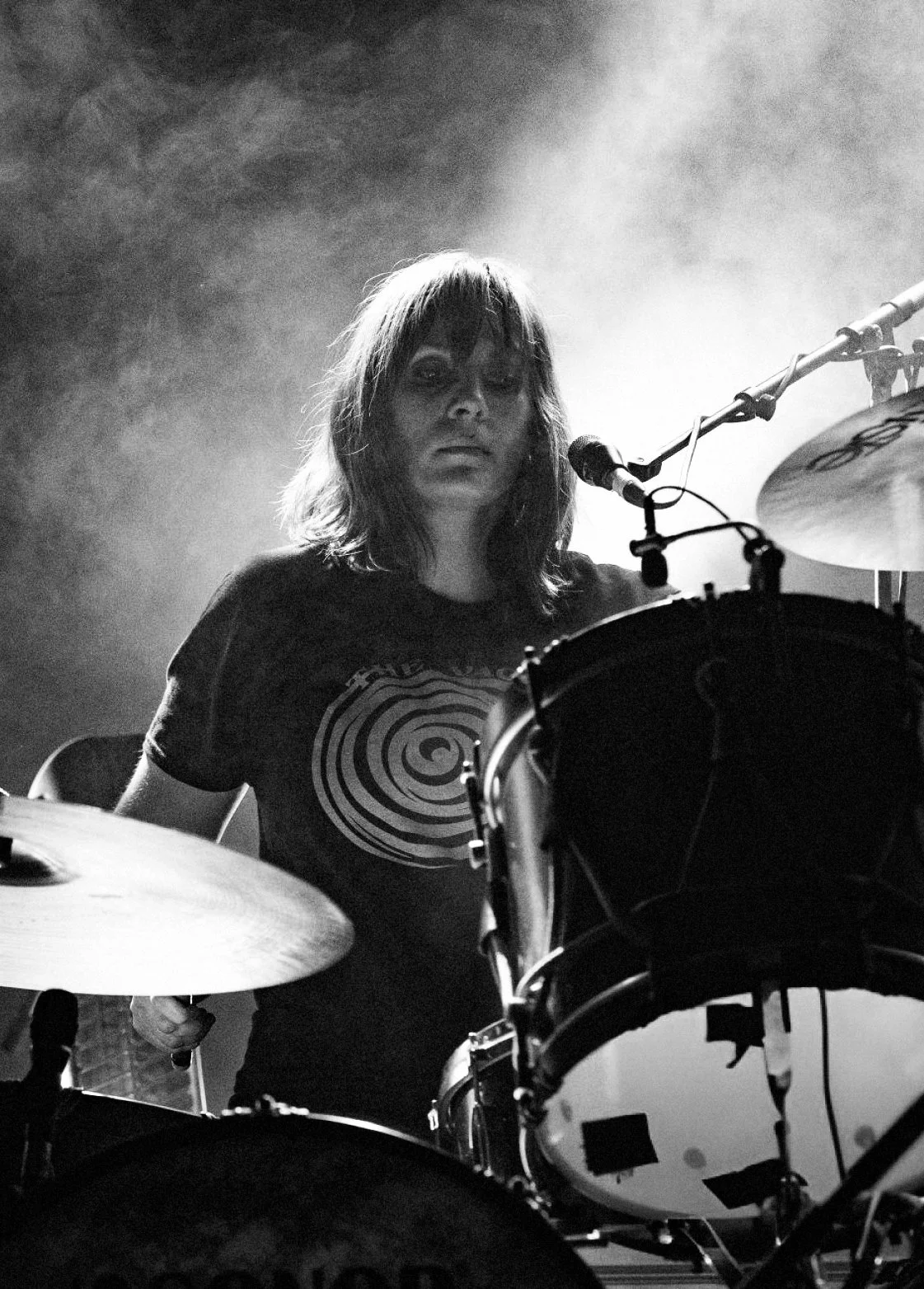

As the uncompromising pulse behind Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, Leah Shapiro drives the band’s brooding, hypnotic sound with a precision and intensity that is at once both strikingly effortless and inescapably mesmerizing.

Onstage, she’s a force of nature, turning complex rhythms into the dark, smoldering heartbeat that propels BRMC’s moody anthems. But beyond the stage, her dedication to her craft and her resilience in the face of personal and physical challenges — most notably her recovery from Chiari malformation and its ensuing surgery — have earned her respect not just as a drummer, but as an artist who unapologetically embodies both vulnerability and strength.

Leah Shapiro’s legacy is one of steadfast authenticity: a formidable musician who proves that power and precision can coexist behind the kit, leaving an indelible mark on contemporary rock and inspiring a new generation of drummers to approach the instrument with equal parts soul and audacity.

BRMC are currently on tour celebrating the 20th anniversary of their landmark album, Howl — a record that remains a cornerstone of their raw, soul-stirring catalog.

KP: You’ve said that you came to drums relatively late — that you were a “horse girl” first — but when you found them, it felt almost effortless, like the instrument chose you. What first led you to drumming, and what do you think it was about drumming that felt so natural?

LS: I was almost done with high school and kind of panicking, like, “Oh my God, what am I going to do with my life?” I couldn’t picture myself having a normal office job. That really gave me anxiety. The whole concept of adulthood was scary. It still is. [Laughs]

Two of my friends were heading to a music school in England, and it was kind of a last-minute decision. I was like, “Okay, I’m going with you. I’ll try this out.” I had tried learning other instruments with very little success, but there’s something about the repetition and trance-like feeling of drumming that really clicked for me. It suits what I’d call my squirrel brain — a mind that’s always turning, always active. Drumming helps settle that down. It’s relaxing.

KP: To speak about that, you’ve described the repetitive nature of drumming as meditative, a way to drift into another world through rhythm. As a guitarist, that struck me as something relatively unique — the drums definitely have this droning quality to them that I don’t believe any other instrument has — I can’t imagine myself getting lost in a guitar riff like that. [Laughs] Can you take us into that headspace — what happens when you lose yourself in that repetition?

LS: Yeah. I think there are two types of playing: there’s rehearsing on your own — trying to learn something new, which can be frustrating — and then there’s playing with the band. I first noticed that meditative feeling with this band in particular.

The role of the drums in our music is to keep everything from becoming disjointed and chaotic, so I kind of lose myself in that wall of sound. On a good night — in rehearsal or on stage — I can just float into the music. My normal thinking brain turns off. Intrusive thoughts stop. It’s an incredible feeling.

KP: Now I want to be a drummer. [Laughs]

You were born in Denmark, but had an American father and spent time living in New York later on. How do you feel that dual background shaped your identity, both as a person and as a musician? And, as a native New Yorker, I can’t help but ask where you lived while you were here!

LS: I started in Boston — lived there for about a year and a half before moving to New York. Now that the guys in the band know me better, they’ve realized the Danish side of me is pretty direct. It can come across as a bit rude sometimes.

KP: Then you were perfect for New York! [Laughs]

LS: Exactly — it gels better with the New York vibe. People are more to the point, no tiptoeing. But yeah, sometimes I have to watch that so I don’t piss people off. I actually didn’t even realize it much until Pete pointed it out — politely — after a few years.

KP: That’s so funny.

In 2014, you underwent surgery for Chiari malformation, which must have been both an incredibly intense and frightening experience. I connect to that on a personal level, since I live with intermittent intracranial hypertension, which shares many of the same symptoms with Chiari.

With neurological conditions there’s often this invisible, almost elusive quality — they affect you profoundly, yet they can be inherently difficult for others to fully see or understand.

How did you navigate that period of uncertainty, both internally and in relation to those around you?

LS: That’s a really good question. During the whole Specter at the Feast touring cycle — about a year and a half — I had no idea what was going on. I felt like I was battling my own limbs. My balance and coordination were totally off. I must have driven everyone crazy, constantly moving my setup at soundchecks.

Getting the MRI was almost a random, lucky accident — stuff like that often gets misdiagnosed. There was real relief in finally knowing what was wrong — I wasn’t going crazy or losing my ability to play.

After surgery, though, there was a learning curve. I had a good outcome, but I had to learn how to trust my body again. Traveling through time zones can make me feel wobbly, which triggers memories of that time — “Oh no, is this happening again?” But it’s not. Still, I had to learn to be vocal about my limits and to take better care of myself.

KP: I know for me, I’d hear my pulse in my head, have double vision, insane pressure, and it took so long to figure out what it could have been. Even MRIs can miss these things unless the right radiologist reads them. It’s frustrating, but there’s power in finally knowing what’s wrong.

Did you face the possibility that you might never play again? Was that something that you thought about?

LS: Yeah, that definitely crossed my mind. I didn’t talk about it much, but it was there. Surgery always carries risk. I met with a few surgeons — one even suggested that I could tour a month later, which was absurd. But I felt confident in the one that I chose.

Afterward, I was worried about so much — how the lights on stage would affect me, how my coordination would be. Our LD at the time, Ben, actually tested me in a lighting room before tour, blasting me with strobes to see if I could handle it. That was about six months post-surgery. It was nerve-wracking.

If I’m honest, I think I’m still rebuilding confidence even now. A year and a half of touring while feeling off — that’s a lot of shows, a lot of little mistakes. Maybe no one else noticed, but I did.

“Enjoy life. Do what you want with it. Don’t follow society’s manual. If something doesn’t align with you, don’t do it. Live your life exactly how you want.”

KP: You guys play such long sets, too.

LS: Exactly. It’s been an extensive process — regaining confidence and the approach that I once had.

KP: Beyond music, what did you learn about yourself during that recovery? Did it teach you anything about resilience, perspective, or how you approach life more broadly?

LS: So much. Mainly, I learned to be comfortable with uncertainty. It’s easy to take normal days for granted. When I got the diagnosis, I went down every internet rabbit hole — watched surgeries on YouTube, read medical journals — and freaked out. I did everything you weren’t supposed to do. [Laughs] Then I spent a few days in bed eating Ben & Jerry’s, got it out of my system, and became practical.

When you have no choice but to face something like that, it’s amazing how much strength you can summon.

KP: I relate to that so much. Lyme disease triggered all of my conditions, including the IIH and POTS. I went undiagnosed for three years, and by the time I finally tested positive, it has progressed to neurological Lyme and wrecked my nervous system. I was bedridden for six years — I lost most of my twenties. I’m 31 now and pretty stable thanks to a beta blocker — thank God for atenolol — but the trauma lingers. It’s hard to regain confidence. Like you said, bad days trigger the old fear — “Is this happening again?”

LS: Yeah, absolutely. I can relate. That back-and-forth must be even harder.

After surgery, I wasn’t allowed to do much for a month — just simple neck movements to keep mobility. Once I was home, it was physical therapy and osteopathy. It gets monotonous. And drumming — probably the most physical instrument there is — isn’t exactly ideal recovery therapy.

Venues always put AC vents right over the drummer, which is a terrible idea for me. So now I travel with a heater. People think that I’m crazy, but it helps. And I swear Thermacare should sponsor me — I go through so many neck wraps on tour.

KP: [Laughs] They should!

Before BRMC, you performed with Dead Combo and The Raveonettes. What did those experiences teach you about being a professional musician, and how did they prepare you for the intensity of joining BRMC?

LS: Sharin [Foo] from The Raveonettes was the perfect mentor. I was young and green, and she was so composed — handling tour management, logistics, everything. I learned a lot just by watching her.

I also played a few shows with Santigold when we opened for Björk. She was incredibly hands-on, in control of every part of her career. That was inspiring.

KP: Oh, that’s so cool!

LS: Yeah! Dead Combo was a wilder, more chaotic experience — but also a learning one. I ended up driving a lot just to keep things from falling apart.

Musically, it was great. Both bands used backing tracks, which can be frustrating, but it teaches you discipline — especially for drummers.

And yeah, my ex, Kurt — who now performs as Null + Void — did electronic Gameboy music. It was super intricate stuff. I had to simplify some parts, but it was a great exercise. I’ve been really lucky to play with such talented people.

KP: Drumming has long been a very male-dominated space — I still think it very much so is, even much more so than other instruments. What has your experience been navigating stereotypes or biases, and how have you carved out your own space within that world?

LS: Maybe it’s my Danishness, but I didn’t realize that it was “a guy’s instrument” until much, much later on. That ignorance probably helped — I was fearless. I remember early on, walking into venues and people assuming I was someone’s girlfriend.

KP: Or the merch girl, right? [Laughs]

LS: [Laughs] Yeah! Or the merch girl. But I’ve been lucky to play in bands that don’t think that way.

I’m not the most technically proficient drummer — I’m not some super drummer like Josh Freese — but I know my strengths. Anyone who thinks that gender makes a difference in that is just ridiculous.

KP: When you joined BRMC, you had to quickly absorb a huge back catalog of music. Is there a particular track — whether for its drumming, its sound, or its message — that resonates with you the most?

LS: Yeah — “Awake.” It connects back to that trance-like feeling. The drums aren’t doing anything fancy, but it’s such a cool song to play. Definitely my favorite.

KP: Thank you for not pleading the fifth on that question. [Laughs] So many do!

You also play songs from the BRMC era before you joined. How do you approach interpreting Nick Jago’s original drum parts — do you stay faithful, or do you feel compelled to reimagine them in your own voice?

LS: First, I locked myself in my Brooklyn rehearsal studio for a long time. The band plays a bit differently live than on record, so I compared both versions. I tried to keep things as close as possible to make the transition easier for everyone.

I had to repeat that whole process again with the Howl album — relearning songs that we hadn’t played live in years. I map everything out in a way that only makes sense to me, but it helps me remember it all. It’s a lot of material.

KP: For women looking to break into rock today, what advice would you give them, either technically or personally?

LS: Don’t be afraid to find your voice and to speak up. I was really timid starting out. Learn to advocate for yourself. And musically — however you approach your instrument, own that. Don’t chase perfection or robotic precision. Develop your own feel. And yeah, practice — one of my friends always says, “Work at your craft every day.”

KP: And, to step back even further: what wisdom would you share with women about life, work, or love?

LS: Oh, God — big question. Enjoy life. Do what you want with it. Don’t follow society’s manual. If something doesn’t align with you, don’t do it. Live your life exactly how you want.

KP: What do you feel makes a provocative woman?

LS: Intelligence. Especially today.