Rio Romeo on Community, “JOHNNYSCOTT,” and Channeling Anger for Good

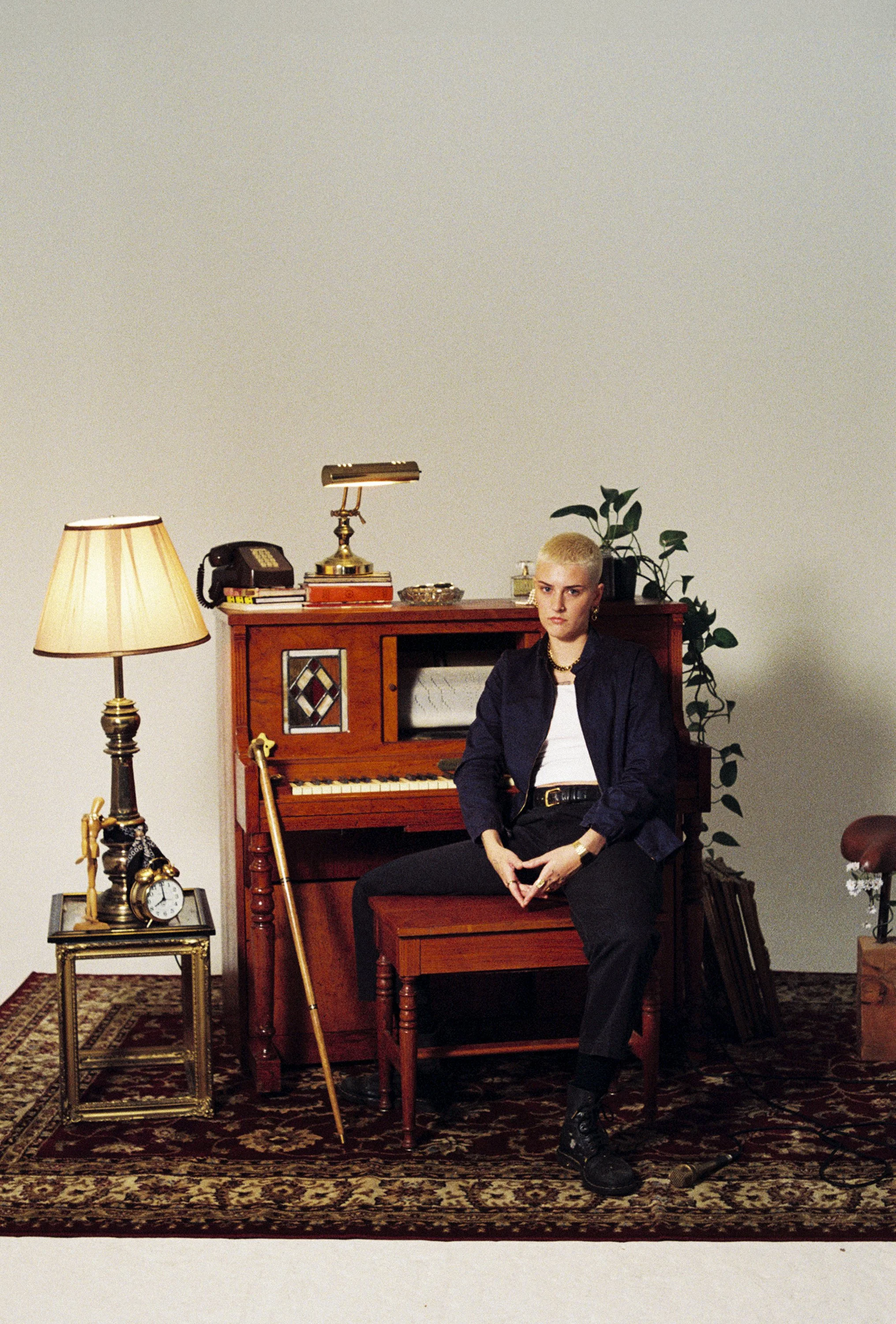

With gritty piano-driven ballads and lyrics that cut straight to the bone, Rio Romeo channels the raw intensity of queer love, identity, and rebellion into every jagged note.

With a punk heart and a poet’s soul, Rio rose from TikTok fame to cult status with tracks like “Butch 4 Butch” amassing millions of streams around the world, redefining what it means to be unapologetically queer in the contemporary world of music.

With fierce honesty and magnetic energy, Rio isn’t just writing songs, but instead reshaping what it means to exist outside the norms — and daring listeners to do the same.

KP: I really hate to be that cliché person to start with this, but I always try to begin chronologically, and it was my first introduction to you years ago... I remember Spotify putting “Nothing’s New” in my Discover Weekly, and I was like, “God, who is this?” It’s an incredible song, but your voice is just spectacular. It says so much without even needing to understand the lyrics.

From a place of selfishness, just because I love that track so much, could you walk us a little bit through its writing and production?

RR: Absolutely! So, I wrote “Nothing's New” in, I believe, 2021. I remember very vividly that I was chewing on this melody, and at the time, I had my piano in the garage downstairs. I lived in a second-floor apartment, so you had to walk all the way out to get to it. The garage is really far away, but I kept my piano there because we had noise fights with my neighbors, so that was the only place that I could play it. It was winter, and it was really cold.

As I was writing the song, I was reflecting on the processing of old relationships and how I felt. I mean, the song is quite literal – it's about going through a relationship that's kind of lost its spark and lost its interest, and you're just like, “I do want this to continue,” but it seems like unless something drastic happens, it's really not possible.

So yeah, I was writing that in this cold garage. The first demo that I recorded of it, you can see my breath. That’s how cold it was.

KP: Oh, wow!

RR: Yeah, so it just felt really vulnerable and really authentic. It was a song that I sat on for quite a while because I was so nervous to share it with people. It was like one of those things where I was like, “I don't really know if I really want to say this out loud.” So I kept it to myself for a while, and then I ended up playing it at this music festival called Viva! Pomona, which is pretty much right down the street from my house. And when I played it, it felt really good to be able to say out loud — it felt good to be able to be vulnerable. So I ended up recording it on my old reliable acoustic piano that I've done most of my recording on, and it went on the Good God EP. I like that song, and I think it's really good.

KP: It's amazing. I'm genuinely so happy you decided to release it because it's so incredible.

RR: I appreciate it. I would say that it’s not surprising, but it's definitely not the song that I thought that everybody would resonate with, especially because I feel like as I was writing that song, I felt really alone in those emotions. And so for that to be the song off of that whole project that reached the widest audience was very telling for me as an artist. It made me realize that I wasn’t alone in feeling how I felt.

KP: You’re definitely not. I think we’ve all been through something like that, so it was great to hook into.

But the sound of it is just amazing, too. I love all the instrumentation.

RR: Oh, yeah! So about the production, too… I worked with a producer named Mike Irish, and I basically gave him this full recording of the track because I knew very little about production. That entire recording of the song is one take on piano and vocals because I didn't know how to do it! [Laughs].

KP: Oh, wow! That's rare today.

RR: Yeah, yeah. Well, I didn't know how to comp. I didn't know that you could just put things together. I wasn't aware that everybody was, like, cheating.

KP: Exactly! Like literally two thousand takes of the same line. [Laughs].

RR: Exactly. So that entire project and that song as well is just one take the whole way through — the piano and vocals were recorded at the same time. So sometimes people want the instrumental, and I'm like, “There is no instrumental!”

KP: That's so funny.

RR: Well, and I have tried to produce instrumentals over the years. Even now, I'm a lot more well-versed with, like, being able to track different instruments. I’ve come into my own as a producer a bit. But I find that with my pieces that I write on the piano, the performances are so tied together that removing the vocals and the story element of it makes me play it differently on the piano. And maybe that's just because I'm not the best piano player, but I really think that the two have to be together. And so even to this day, if I'm recording a song that is particularly dynamic or whatever, I'll record both the piano and the vocals at the same time.

KP: Yeah, that's awesome. It's very unique today.

Your newest single, “JOHNNYSCOTT,” speaks of you metaphorically shooting a man that groomed 19-year-old girls, and you said that “at one point, [you] were one of them.”

When I got the press release, I immediately hooked into it. I lost one of my close friends due to the effects of sexual assault years ago, and I founded a new company of mine called Uppercut in her honor, where we’ve teamed up with some of the greatest female MMA fighters and boxers in the world to teach women strength training and self-defense via an online platform.

As someone who has relentlessly been assaulted on the street multiple times – and broken a nose and chased many down through New York City traffic like a crazy woman – it’s something that I’m incredibly passionate about.

But in a country – and a world – where sexual assault is so difficult to persecute, I really do feel that the only protection we have is our own self.

I don’t really have a question here; I just think it’s important to give you the space to speak to the inspiration behind the track and the experiences that you went through.

RR: So this song was written about this one local guy in particular, because I live in Pomona, right? I have this whole scene of young artists and creatives around me, and we all would hang out in this one spot. And there's this one guy that was just very notable in his interests and relationships with specifically 19-year-olds.

KP: Weird.

RR: So weird.

KP: Only 19-year-olds.

RR: I mean, give or take a year, but that's the rep. And everybody that I know that went through a similar thing also was 19 when it happened to them. And he was at least 10 or 15 years older, right? And so I knew that I wasn’t alone in this experience because the same thing happened to a bunch of my friends. The guy really ran circles. It even got to the point where if he showed up at local music gigs, he'd be kicked out immediately. He had a huge rep of being a groomer and really just a creep.

And so anyways, fuck him, right? I think that this song was originally written because I was talking to my partner about him and all of the fucking creepy-ass guys that are in a similar circle to him. She was like, “You know what? You write a lot of music, but it's not really ever very angry. You should really try writing an angry song because I feel like you have stuff to be angry about.” Literally that same night, the song was finished. I wrote, recorded, and produced the entire song that night. It was the best suggestion ever, and that's just her being an incredible partner and knowing exactly what I need. It was so cathartic. And now I get to sing this song on stage! I feel like it's so much more, I don't know, satisfying and fulfilling to be able to be like, “Yeah, fuck you. You're a shitty guy, and I hate you with all of my heart,” rather than being like, “Oh, I'm really sad,” you know? And like, of course, there's room for that emotion of sadness.

But especially at this point in my life — I'm 26 now — I don't even know why you would even want to talk to a 19-year-old. We're just in such different places in our lives. And that's kind of where the conversation started of just being like, this is insane. I'm older now, and I have a truer perspective on just how fucking creepy it is. It feels really good to be like, yeah, you're awful.

KP: Totally. And that kind of leads us into my next question, because you also said that, “Writing angry music was quite different for me, because I was raised in a really conservative Christian environment. Anger is not something that women are allowed to feel, and that’s been drilled into me, even in my years out of those circumstances.”

I wouldn’t say that my upbringing was extremely conservative, but I was raised Catholic, so much of the same guidelines for women remain true.

Anger is extremely important. In my personal beliefs, I don’t think that we will ever end rape culture or grooming culture without it. When we think about all of the revolutions that have taken place in this world, many were spawned via anger or physical action over peaceful protest. I wish that it weren’t true, but it is.

What changed within you to write this track? What allowed you to begin to not only feel that anger but also channel it into music?

RR: Well, I think that part of the difference for me personally between being able to make angry work versus being able to make sad work is that I feel like angry work really owns the emotion. It's loud, and it's a lot more defiant about the circumstances. When I feel like when you're writing work that’s sad, it's just like this acceptance of it, right? Like, this is the thing that happened to me, and I'm left to deal with that, right?

I think that had I not been financially liberated and gotten agency over my own life away from my conservative family, I really don't think that I would have been able to say any of that, because it's risky. Being angry is risky, especially as a woman — especially as somebody that still needs their family. You can't really do that. You just have to accept things the way that they are and deal with them.

I think that the anger is a place of growth for me because I feel like I can finally say what I need and want to say. I'm ready to face the repercussions of it, and that is not a privilege that I always had.

KP: I think that’s a great point.

You got into a terrible skateboarding accident back in 2020, which left you with a brain injury and chronic hip problems, so you’ve said that shooting this video was you finally taking advantage of your improved mobility.

I was diagnosed with Lyme disease back in 2018 and experienced a cascading amount of complications from it – mostly neurological and cardiac – for many, many years.

RR: That’s really hard.

“I think that the anger is a place of growth for me because I feel like I can finally say what I need and want to say. I'm ready to face the repercussions of it, and that is not a privilege that I always had.”

KP: Yeah, it was hard. The peripheral neuropathy impacted my guitar playing for five or six years, and I feel very much like a beginner all over again, even though I started playing when I was six. It strips a lot away from you.

How did you remain optimistic during such a difficult time? What kept you going? What advice would you lend to anyone who is also going through the difficulties of physical limitations?

RR: Well, for me, I was in a little bit of a special circumstance when I got into my skateboarding accident. Because, one, I had just met my partner, and we're still together. So we were in it together — it was like this really great honeymoon stage while I was dealing with literally the most painful and hardest thing ever. But that made it a little bit sweeter and more tolerable for me.

And then also, throughout my whole journey of getting in this accident — being really physically limited in what I could do and experiencing all this pain and discrimination in the medical system — I think that the big rock for me was that I had all of my fan base and this giant community of people that are queer, that are disabled, that know exactly what I'm going through. They literally supported me not only with advice but also with actual dollars. So many people sent me $1 or $5 or whatever in my greatest time of need.

So my circumstance of going through this incredibly difficult period of my life was also met with so much sweetness and tenderness and support.

But I would say that the best piece of advice that I could give is to find your community and really lean on it. Like, even in the grocery store — I remember I used to wear KT tape on my unaffected leg because my knee was overcompensating, so it would hurt, and quite a few times, older people would come up to me and be like, “What is that? It looks like it's medical.” And I was like, “Yeah, it's because my knee hurts. It's supporting the muscles or whatever.” And they'd be like, “Oh, that's so cool. I'm going to try that out. My knee hurts, too!” [Laughs]. So many people are a part of the disability community. So many people are affected by chronic pain. So many people know people and love people that are going through something similar. You'll have something in common with a large group of people — it's just about being able to find that community and really tap into it. That's really the thing that helped me get through such a challenging time.

KP: It’s super important.

I’m so in love with your sound, which you classify as “cabaret punk.” It’s a very unique genre that I think very few artists have been able to hit on the head – I think the only other act that really comes to mind with nailing it well is Amanda Palmer and the Dresden Dolls. I really do love it, though.

What led to you exploring this sound sonically, or what was it that drew you to it? It works so well for you and your voice.

RR: Thank you. Well, let's start from the beginning. I started doing musical theater at a young age, right? And I was never good at being a part of musical theater. [Laughs]. There's all these, like, nine-year-olds that have been going through vocal training their entire lives, right? And I'm so not there. [Laughs]. I auditioned for all of this stuff but always got turned down because they were just like, “You have a weird voice. That's not what we're looking for in Annie, or whatever.”

KP: I think that would be cool! I think they really missed out on that. [Laughs].

RR: It’s okay! I mean, I feel like at that time, they were probably pretty valid. I've really grown into my voice and found a style that works for me. But trying to sing more commercial things? I think it sounds weird. So they were right — I would give that to them.

But yeah, so I started there, and I thought it was really interesting and really cool. It was definitely my personal thing. It was my music. And, you know, it wasn't, like, church music — it wasn't my dad's 80s rock music. It was my thing. And so that felt really cool to be able to be a part of this community. I felt like I had agency over the music that I was consuming and singing.

And so time goes on, and then as a teenager, I spent a lot of time in the DIY scene, like, in the Inland Empire and L.A. area. But it was a lot of guys with guitars playing shoegaze. And I always thought that was really cool and really interesting, but I was not a guy with a guitar, and I didn't play shoegaze. So I really felt that there wasn't any space for me in the scene.

I still wanted to be able to make music, but I felt like I didn't really have a lot of real-life examples of people that I had anything in common with that made music. And so when I went to DePaul University at the theater school for one quarter before I dropped out...

KP: That's how you do it.

RR: Yeah, I went for set design.

KP: I got a degree. I wasted four years. Don't be like me. [Laughs].

RR: Yeah, no, I got out of there pretty quickly. I was like, “I don't think this is for me.” But while I was there, it gave me a lot of time to be able to just chill around a bunch of pianos. And that was really the jumping-off point of how I found my sound. I wanted to be a part of this theater world, but I don't want to be an actor, and I don’t want to be, like, a musical theater singer. That's definitely not for me. But I do enjoy writing the music, and I enjoy being a part of it and putting my own spin on it. And watching all of these guys with guitars play shoegaze over the years made me want to make music, too. And so it was this natural progression. While all of my friends were in rehearsals for acting and stuff, they would come back, and I would be like, “Hey, I wrote a funny song. Do you want to hear it?” It really started in this way of comedy. It really just started as a way to make my friends laugh. I wasn't really writing these hard-hitting emotional ballads right off the bat. It was very much like a, “Haha! Want to hear what I did?” It was really fun. I enjoyed showing people, and they liked it.

But then as time went on, I found a lot of ownership over that and, like, being able to play the piano in the way that I wanted to because I taught myself. I had limited capability, which made me have a really specific sound. And also with my voice, I felt like it was just this thing that had no rules because I really didn't feel like I had any examples for it.

I actually didn't know about the Dresden Dolls or Amanda Palmer until I had already released “Butch 4 Butch,” and people were like, “This is just like them.” I was like, “Oh, it is?!”

KP: That's crazy, because I remember when I first heard your music, that was one of the first things that I had thought of — we spoke with Amanda Palmer a few years ago, so I'm a fan of hers. But it's so cool that you could come into that kind of sound without even really having been exposed to them yet.

RR: Yeah, yeah. It was definitely like a, “Wow, this is like crazy how similar it is.” But, like, I swear, I didn't even know.

KP: It's cool, too, because it's such a unique sound.

RR: Yeah! And I think the sound really comes from, like, for example — my first song that I put out that I had any sort of hand in the production of was a song called “Do You Like The Girl in Red?” Which is “Dyltgir?” on streaming. It has all of this layered percussion, all of this layered piano, and a lot of layered vocals. It's just kind of all over the place, and it definitely has a cabaret punk vibe, if there was, like, a full cast, right?

I produced that in a way that I would never again. I produced it the hardest way possible, where I recorded, like, every single track that I did with percussion, with vocals, whatever, as a full recording, because I didn't know how to use this stuff, right? So it gave it, like, a really raw and authentic sound — that’s the only way that I knew how to do it.

So I think that my limitation in terms of production started me on a unique path with the piano because I could only use what was physically around me. I had no desire to do anything else.

KP: Yeah, I think my favorite artists ever usually come from this place of having an actual lack of formal education, which makes your practice so interesting. I come from the fashion world initially — I remember working with so many photographers whose shots would be so beautiful, but they'd be like, “Oh, the exposure is slightly off. Let's retake it again.” And I think in those moments when you’re trying to achieve perfection, you totally lose the magic.

I had a solo photo exhibition back in 2016, and I was never formally trained in photography. A lot of the work came out looking really experimental, and people would say, “How did you do that?” And I was like, “I don't fucking know! I just did it.” [Laughs].

So I think I always say, especially when it comes to art, you can't unlearn what you've learned, right? It lends itself to much more interesting work, in my opinion. I love your path.

RR: Thank you. But I think that even with, like, “Nothing's New,” if I were to write that song again today, I would write a much more complicated song. I've become a better pianist. I've become a more complex songwriter. But that song is really simple in a way that's really to the point.

So, yeah. I totally agree that there's magic in the imperfection. And also there’s a lot of magic in being okay with what you make because you're like, “This is just the best that I can do.” Like, my song “Over and Over” — which I was talking about a little bit when we were talking about “JOHNNYSCOTT” — is also a song that I made the hardest way possible, but it made a really unique song. It was also, like, 60 tracks or something — and all of them have different vocals. I don't know if I will ever make a song exactly like that again, because I've just learned how to do it in a more efficient way.

KP: That makes a lot of sense.

In an interview, you said that you want to create music “for everyone,” which I think is so important. As a gay woman myself, I think my biggest issue with the community is that we tend to stay so insular – and I understand why, but it’s also incredibly limiting. I want the community to break through – I want us to be seen as artists, not just gay artists. I want our success to be limitless.

What was behind your decision to create genderless music “for everyone?”

“At the end of the day, when I’m writing music, it’s primarily for myself. It’s a way to process. And if I share it, then I hope that it resonates with the lesbians. But I also hope that it resonates beyond my circle, too.”

RR: I think that it really started in a place of my super-specific experience of having a butch partner and thinking to myself that there's not enough work out there that has any other sort of gender dynamic to it than a beautiful woman and a strong man. So it was like my little space of what I would like to see, what I feel would represent my relationship, what would be true to my love. I think that it’s important to be able to have everyone's voice out there in the world.

And I think that, yes, it's for everyone in the way that even though “Nothing's New” is about a gay relationship, everybody can understand it and feel the same way. I don't want to be closed off in a way where I’m telling people that this music isn't for them.

At the end of the day, when I'm writing music, it's primarily for myself. It's a way to process. And if I share it, then I hope that it resonates with the lesbians. But I also hope that it resonates beyond my circle, too.

But I think that creating work that can be transformed from person to person and feel the same — to not feel exclusive — is cool. But I also think that there is value in being like, “This is for the lesbians.” I stand on that, but I don't know if I stand on that quote for every single song, if that makes sense.

KP: Yeah, totally. I think what's important is to have a blend — to have your discography be able to resonate with everybody, even if it is dedicated mostly to your community. I think it's important to always create stuff for your community as well, just in terms of representation and allowing people to see different types of love.

RR: I still get comments on my TikTok all the time of people being like, “Am I allowed to listen to ‘Butch 4 Butch’ as a straight man?” And I'm like, “Sure, I don't care if you like the song!”

KP: Give me those streams! [Laughs].

RR: Yeah! Or people will be like, “Am I allowed to come to your concert if I'm a straight man?” And it's like, “Yeah, but you better be really fucking nice to all the lesbians.” [Laughs].

So I think that there's a lot of value in being able to tell your story. But inherently, that story is going to resonate with whoever, right? Like, you can never choose that.

KP: Right.

RR: And even if you make the most specific shit in the whole world — I wrote a song called “Missus Piano” about literally missing my piano because it was in a part of the house that’s less accessible for me to play. But people have been like, “This is about love!” Sure, yeah. “This is about your girlfriend!” It's about my piano that I missed in the room!

KP: [Laughs]. That's so funny.

You said that you discovered the power in your voice after you moved out of your parents house and became homeless, spending “a lot of time in [your] car where [you] didn’t really have anything to except sing.”

Did you always know that you could sing, or was that a happy accident byproduct of moving out? What advice would you give to people who want to find their voice, literally or metaphorically?

RR: I still don't think of myself as the best singer. I just think that I do the best with what I have, and it really fits my style. But like, do I think of myself as like a vocalist? Not really.

I think that I was really able to find my voice in a way where I feel confident that the work that I'm making is fitting the style in which I'm singing, if that makes sense. And I think that I'm always becoming a better vocalist, but like, I've always enjoyed singing. It's always been something that is cathartic, therapeutic — I really enjoy the literal breathing exercise of it.

I think that being able to feel comfortable in my voice — not having to sing in this soft, you know, gorgeous high way — I can sing in whatever way that I want. If it feels good to me, then that's enough. And it was really awesome that people also enjoyed that.

KP: Also, your voice is so unique, you know? For me, when I think of my favorite singers, they're not maybe the singers that have the most range — that's not what I personally want to hear. I would much rather listen to a singer that has timbre or rasp or emotion, you know? Something like a very unique voice, which I think you have. I think it's so much more fun to listen to.

RR: Thank you. I appreciate that. But to say that I always knew I’d be a singer — I don't know if that's necessarily true. But I will say that from a very early age, I did carry a little karaoke microphone around the house with me and sing into it.

KP: Okay, that's good enough. [Laughs].

RR: I think that I always enjoyed it, but I never really put very much pressure on it.

KP: That’s the best way.

In 2021, you said that you had a collection of over 400 “lewd” magazines – which might even be more by now. I have a collection, too, but I’m not a match for you because I think mine tops out at maybe 100. [Laughs]. I used to do a lot of mixed media collage work back when I was in college, and I just never parted with them after that.

What draws you to them, and how did that collection start?

RR: Okay, so I have a unique phenomenon about me where people give me shit, right? I have so much shit, and I feel like I've paid for very little of it. This was just a classic, right place, right time, right guy. I was working at a place right next to this old guy — he was moving out of his business, and I think he sold old train model collectibles or something. His business was abstract to me, but his kids were retiring him or moving him out or something. But they came across all of his collections over the years. I was like, talking to him, shooting the shit, and he was like, “Do you want this?” And I was like, “Sure, let me take a look.” And so he brings me into his office, and he literally just has a huge, huge, huge stack of all of these boxes full of magazines. I was like, “I can't say no to this!”

KP: That's crazy.

RR: So even when I was homeless, I got a storage unit just so I could keep these. And then as I spent more time with all of the magazines over the years — because this is basically like 1967, I want to say, to the early 2000s — like every publication of Playboy, Hustler, and a couple of others.

KP: It's expensive! It's a lot.

RR: Yeah. And it's something that I would never buy. But yeah, now I have grown to appreciate the high level of — this is going to sound so fucking stupid because it's a porn magazine — but I've grown to appreciate the level of photography and intentionality. Even looking at the old ads — there’s a lot of interesting political articles. They're much more than porn.

KP: Yeah, no, they are. So like I said, I was doing a lot of mixed media work in college, and I wanted to use actual old paper for it. Well, I mean, I don't have people gift me the way that people gift you things, so I had to go on eBay like a peasant and pay like a pretty penny for them. [Laughs]. They're fucking expensive! But when you go through them, it's so fascinating because back in the day, very notable photographers would shoot for them. And they really do have important articles in there!

RR: Yeah, there was one that I saw from the 70s that was talking about gun control. It was so interesting to be able to read what the take was like at that time. And there are a lot of really well-respected, very famous celebrities over the years that have been involved in some sort of way. It's really interesting. And it's also just such a lost media. Like, obviously, people have the Internet now, so nobody's buying that. But it's just so interesting to see what our parents and grandparents and whatever have been looking at all those years.

And that also ties into me being a collector of many things, like an archivalist, I would say. That's where my love of it really started to kick off, just like being able to really spend time with it and see the value and see the importance, to understand more about the world around me.

So we got a player piano, and now I have an entire crazy amount of old player piano scrolls. And it’s really interesting because you get to hear all of these compositions from pianists over the years of popular songs — all of those compositions are different. We were listening to “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head” yesterday, and we happen to have two scrolls of it and they're done by different composers. It's so interesting to hear a different musical take on it.

So yeah, it just really led me to this place of deep appreciation for the shit that nobody is looking at anymore.

KP: Yeah, absolutely. I'm definitely a collector. I've collected so many things through the years. When I was a kid, I used to collect sports cards because I was a big athlete at the time. I had thousands and thousands of cards — you don't even know. I used to buy them, sell them, and trade them — I made money off them.

RR: Oh, yeah?!

KP: I know! But now in my older years, it's just become a lot more niche. It's funny, you know, when you say that you would pay a lot for something that other people would be like, “What the fuck?” I collect things specifically from one of my favorite movies. Actually, it might be my favorite movie of all time — David Fincher's The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo from 2011 with Rooney Mara. I collect memorabilia from that film that seemingly nobody else wants. I have like four different pairs of pants that Rooney wore in the film, and my girlfriend is always like, “How much did you pay for those?” And I'm like, “I got them for only $1,000!!” And she's like, “Nobody would pay $150 for that.” [Laughs].

But it's cool to collect things that mean something to you — they don't have to mean anything to anybody else.

RR: Absolutely. And I think that if you're going to collect, you might as well be able to count on it on a rainy day. When I was going through my skateboarding accident, I had all these magazines. I did picture framing for many, many, many, many years of my life, so I bought a bunch of picture frames and framed all of the magazine covers and started flipping that. And that actually helped us eat and feed our cats for a while.

KP: No, definitely. It has so much value.

What advice would you lend your younger self?

RR: I think that what my younger self could have really heard was that my experience is not unique. I think that especially having such a turbulent time with my family and my queerness, I think that I could have found a lot of relief and a lot of hope through knowing that so many queer people have had a really shitty time too but have come out of it on the other side — happy and full of life. Growing pains are just a part of it. That's a really big part of so many people's stories.

I think that I really could have heard that I wasn’t alone in this experience. That I actually wasn’t special because of this experience. It happens to people all of the time, and you just need to find people that have gone through this too and lean on them.

KP: I think that's great advice.

What do you feel makes a provocative woman?

RR: I think that my relationship to womanhood is so colored by growing up in a conservative household — growing up specifically in a very Christian environment. And I think that when I'm thinking of a provocative woman, it’s someone who is loud and it’s someone who is willing to not care — but specifically to not care about what men think.

I don't really identify as a woman, but I think that in the eyes of many, I am living the provocative female lifestyle of being loud and being in charge of my own life and not giving a fuck about what men have to say about it.