Roberta Bayley on Photography, Punk, and the Greatest City in the World

In the dimly lit clubs of 1970s New York, amid the clang of guitars and the restless spirit of punk, Roberta Bayley stood quietly behind her camera, immortalizing legends before they became legends. Through her fearless eye, the punk revolution found its most iconic defining vision.

Starting out in New York as a doorperson at the famed CBGBs, Bayley quickly transitioned behind the camera, becoming one of the era’s most vital visual historians. Soon after, she began working as the chief photographer for Punk Magazine, capturing the raw, rebellious energy of groundbreaking artists including the Ramones, Blondie, Richard Hell, and Johnny Thunders. Her candid, unfeigned style mirrored the DIY ethos of the movement itself, and her images — including the legendary cover of the Ramones' debut album — helped define how punk would be seen, remembered, and mythologized for years to come.

Over decades, Bayley’s photographs have been exhibited internationally, published in countless books and magazines, and remain some of the most enduring documents of a cultural revolution that changed fashion, music, and art forever.

KP: I am so overwhelmed — in the best way — by your iconic career and all of the incredible moments that you got to document that then became a part of history forever. I think it’s fair to say that generations like mine would not have the understanding of punk that we do without your photographs lighting the way.

But for those that are unfamiliar with your work, can you take us back a little bit to what first drew you to photography? How did you get involved in it? What brought you to New York, and what about it made you stay?

RB: I had an interest in photography from an early age, but I didn’t know it. Like many families in the 50s and 60s, my family subscribed to LIFE Magazine, which arrived each week, featuring renowned photojournalists such as Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, Lee Miller, Gordon Parks, and countless others who covered everything from war to Hollywood. We also had a book at home that I was fascinated by called The Family of Man. I realized much later that it was actually a catalogue for a photo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955, curated by Edward Steichen, which featured 533 photographs by 276 photographers. It fascinated me — I looked at it over and over, and the book is still in print! Fashion magazines like Seventeen also obsessed me — little did I know that many of the covers were shot by Francesco Scavullo or the team of Allan and Diane Arbus! I just loved looking at images. It took me until my early teens to put together the idea that you could actually “take” photos yourself. That was the time of simple amateur cameras like the Instamatic, and everyone took family photos with those cameras — it was just a part of life. It wasn’t particularly serious, but it was fun.

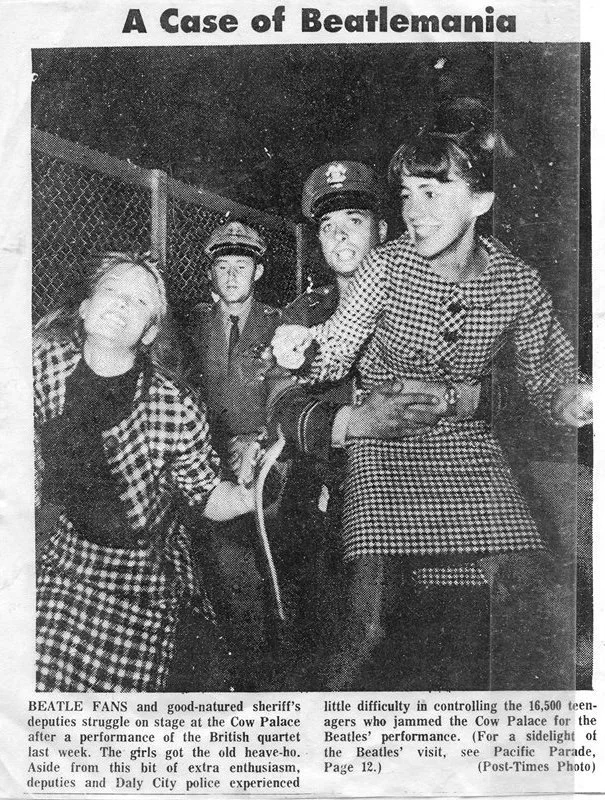

Then the Beatles came along… Everything changed for me in February of 1964 when I first saw a short film on late-night television of the Beatles performing in London. A total obession began. Some of my earliest “rock photographs” were taken of the television set when the Beatles were on! I also took photos of photos of the Beatles by photographers like Robert Freeman. Early appropriation? Who knew that would be a thing! I did see the Beatles play live 3 times, but the experience was much too intense to even consider taking photographs. When they came onstage and throughout their 28-minute performance, the flashbulbs from the fans’ cameras lit up the vast hall as bright as day, and the deafening screams blotted out the music. A perfect experience.

As a teenager I saw The Rolling Stones many times, The Kinks, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, The Who, Sonny & Cher, Buffalo Springfield, Moby Grape — just everyone you can imagine. My favorite groups were the Byrds and a lesser-known band, the Flamin’ Groovies. The 1967 Summer of Love was in full swing in San Francisco, and we went to The Fillmore and Avalon Ballrooms as much as possible to see all the bands of the psychedelic era — Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, The Doors, Quicksilver, Moby Grape, and The Grateful Dead.

When I was 16, I took a photography class in high school and learned to print my own photographs. That’s when the magic really happens — when you’re in the darkroom and see the image that you took come up in the chemical “soup” right before your eyes, like magic. I learned that I had a good eye for photography and started taking it more seriously. When I was in college, I bought a used Nikon and started experimenting, taking pictures of friends or on the street, but not having a darkroom made it hard to pursue.

In 1971 I dropped out of college, sold the Nikon, and moved to London. I wasn’t involved in the music scene there at all. I worked briefly for Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood in their shop Let It Rock on Kings Road and had all kinds of odd jobs. I travelled a bit in Europe, Greece, and Turkey. Then, in 1973, I met Ian Dury, who was in a band called Kilburn and the Highroads, and we began a romance. That ended in 1974, and I bought a one-way ticket to New York.

I literally knew no one there, but I had a list of people to look up that friends in London had given me. Everyone was welcoming, generous, and wanted to show me around. One guy asked me if there was a band I wanted to see, and I said The New York Dolls, because I’d never seen them. We went to their show at Club 82, and afterward my friend had a party for them at his loft, which was right above the club. That night I met a few people from the downtown music scene and immediately forgot about my plans to go back to California. It was obvious to me that something was going on creatively in New York — there was just a great energy and excitement that I hadn’t found in my 3 years in London. I found a place to stay and got a job.

KP: Wow, that’s so incredible. You also did the door at CBGBs, which might be one of the jobs I’m most envious of in all of history! [Laughs]. How did you come to work at Hilly’s?

RB: Eventually, I met Richard Hell, and we became a couple. He was in a band called Television, which was just beginning to play Sunday nights at a new club called CBGBs. The manager of the band asked me if I would sit at the door and collect the admission fee of $2. At the beginning, the take might have been $40. Most of the people got in for free, as they were friends or other musicians. Maybe 25 people would show up on a good night. Little by little the club started getting more attention, and the crowd got bigger — especially after Patti Smith did a residency there with Television, and the Ramones began building a following.

After Richard and I broke up, CBGBs owner, Hilly, asked me to do the door regularly. It was enjoyable, and I became friends with all of the newly formed bands — the Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads… So many bands wanted to play there; the floodgates really opened. People who came to see a band would have their own band three weeks later. There were no other clubs where bands with original music could play but CBs and Max's. Nobody had record contracts yet, and the door take was still pretty small — as was my salary — but it was a lot of fun. In November of 1975, I bought a used camera and began to take photos.

“That, to me, is the essence of punk. Don’t wait to be an expert or to be given permission — just do it.”

KP: That was definitely the right decision. You were the chief photographer for Punk Magazine, which was probably the most seminal punk publication in the world at the time. How did your position there come to be, and what did you learn from your tenure there?

RB: At CBGBs I met the guys from Punk Magazine, and they asked me to shoot a story for them. We hit it off, and I soon became the chief photographer for the magazine. Punk had a different way of covering the music scene — it was very funny and irreverent. In the beginning, the whole magazine was hand-lettered! No one had any money, which is something that often spurs creativity. It was great fun working for Punk; everything was unpredictable. We did these things called “fumettis,” which were basically photo comics. Two of the issues were complete stories — The Legend of Nick Detroit starring Richard Hell and Mutant Monster Beach Party starring Joey Ramone and Debbie Harry. Everyone in the downtown scene had parts — it was kind of like making movies.

KP: That’s incredible! And speaking of Joey Ramone, probably one of your most recognizable photographs was the cover of the Ramones’ self-titled debut album. My uncle was a drummer and used to play with them at CBGBs. I remember stories of them going to my grandparents’ house in Brooklyn after gigs — I’m positive that they had no idea of the immensity of who was in their basement at the time! [Laughs].

Did you know that that photograph — or any of the photographs that you ever took — would become the phenomenon that it came to be?

RB: We didn’t take things too seriously; we just did it! That, to me, is the essence of punk. Don’t wait to be an expert or to be given permission — just do it.

KP: That’s some of my favorite advice that anyone could ever lend. Do now, learn and make magic as you go.

For some reason, your photographs from that era feel so alive. There’s this photo you took of Richard Hell in his apartment from the Destiny Street album cover session that feels like I could step right into it. I’ve seen others say the same about your work as well, that it just has this very living quality to it, and perhaps that’s why it feels just as visceral to people today.

Can you put your finger on what that’s about? As someone born in 1993 who very much so wishes she was born in 1963, it’s something that I’m ever-grateful for.

RB: I have to say, my photographs were never planned out. Not much “thought” went into them. I just took the picture. Anytime I thought too much, the photo was less natural and more awkward. I was working mostly with people that I knew, in some cases good friends. Things were pretty spontaneous. I almost never directed people, or asked them to pose. It was very organic; I guess that was the origin of my “style” — not having one! I think that I was most influenced by photojournalism — taking photos of what was happening without directing it.

Maybe that’s why you say my photos are like stepping into the moment — I consider that a high compliment, like the person who is looking at the photo is me! Those are the kind of photos that I like to look at — where you completely forget about the photographer, and it’s just you and the subject. No middleman.

When I did actual “photo sessions,” sometimes other people were directing. On the Ramones session, it was for Punk Magazine, so John Holmstrom, Legs McNeil, and the Ramones art director, Arturo Vega, were there, but nobody was really telling me or the band what to do. The most that was suggested was moving to a new spot, just to have a different background. We were just fooling around; there was no pressure. It wasn’t a shoot for the album cover, just for Punk, which wasn’t exactly Rolling Stone. We were all just friends.

Richard Hell often had “concepts” and ideas for the photos that he wanted me to take of him, the Heartbreakers “blood” photos and the Blank Generation cover photo being the most obvious.

KP: All as iconic as the next! Later on, you appeared in Downtown 81 as a hooker, which was one of my favorite films when I was younger. How did that come to be?

RB: Downtown 81 was written by my good friend, Glenn O’Brien, and directed by another friend, Edo Bertoglio. They basically cast everyone on the downtown scene. I remember I was up half the night and had an 11 a.m. appointment for “hair and makeup,” but I made it. I’m wearing more makeup on that shoot than I wore in my whole life! I knew Jean-Michel, and it was a fun shoot. Of course I was crestfallen when I wasn’t nominated for best supporting actress, but I’ve come to accept it.

KP: [Laughs]. It’s a really great film. As a woman in a very male-dominated field — and a male-dominated scene — did the fact that you were a minority ever strike you? Did you ever feel that you were treated differently for it? What advice would you lend to women who want to enter photography today?

RB: I never thought about the punk scene as being “male-dominated.” Rock and roll in general has always been quite chauvinistic, but I think around that time, things were beginning to change a little. Not necessarily in the music business, but in the music scene. There were lots of women beginning to be more than “just” singers — they played instruments, formed bands, and wrote songs. And the women hanging around weren’t just groupies — and the ones who were groupies were pretty cool — they were often creatives: journalists, illustrators, poets, fashion designers, band managers, and, yes, photographers!

KP: And thank God for that! I’m glad that you didn’t share that view with other people.

As a native New Yorker, I feel like all we ever hear is how the magic of New York is gone, but I’d beg to say that a lot of it has just moved out of Manhattan! A lot is still there, of course, and its energy and history will always remain, but some of it has also spilled into Brooklyn and Queens with venues like TV Eye and Lucky 13.

As someone who was here through what I consider its golden era, though, do you feel like the magic of New York is gone? Could it ever really be?

RB: It’s very funny that people think of 70s New York as the “golden era.” The only reason for that is that many neighborhoods in the city were so run-down, dirty, decrepit, and crime-ridden that no one wanted to live there! So it was all older immigrants, Latinos, and drug dealers. Anybody that could afford to, left. But because the neighborhood was so undesirable, the rents were low. So who moved in? Artists. Those neighborhoods are often the most interesting and diverse. The South Bronx was the poorest and most desolate, bombed-out neighborhood in all of New York in 1979, yet it produced rap and hip hop — now the most dominant popular music in the world.

I still live in the same apartment that I had in 1975. Yes, the neighborhood has changed, some things for the better, some not. But it’s still the best city in the world. The streets are still vibrant, and I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else.

KP: I couldn’t agree more. If you could say something to your 20-year-old self, what would you tell her?

RB: My advice for any photographer, man or woman, is the same: shoot what you love, what inspires you, and have fun. As long as you’re enjoying yourself, persevere. If not, quit! Make room for somebody else. As for career advice or tips on “being successful,” I have none. I never made a living from photography; I just didn’t want to take pictures of people I didn’t know… Except for Prince. But he never called.

As for what I would tell my 20-year-old self? It’s the same thing that I tell my 74-year-old self: say yes, have fun, be spontaneous, eat well (no meat — I’ve been vegetarian since 1969,) drink good wine, have as much sex as possible, and be generous to the less fortunate. Fall in love at your own risk.

Title photograph: Bobby Grossman