Wendy James on Rock and Roll, Transvision Vamp, and Turning Provocation Into Power

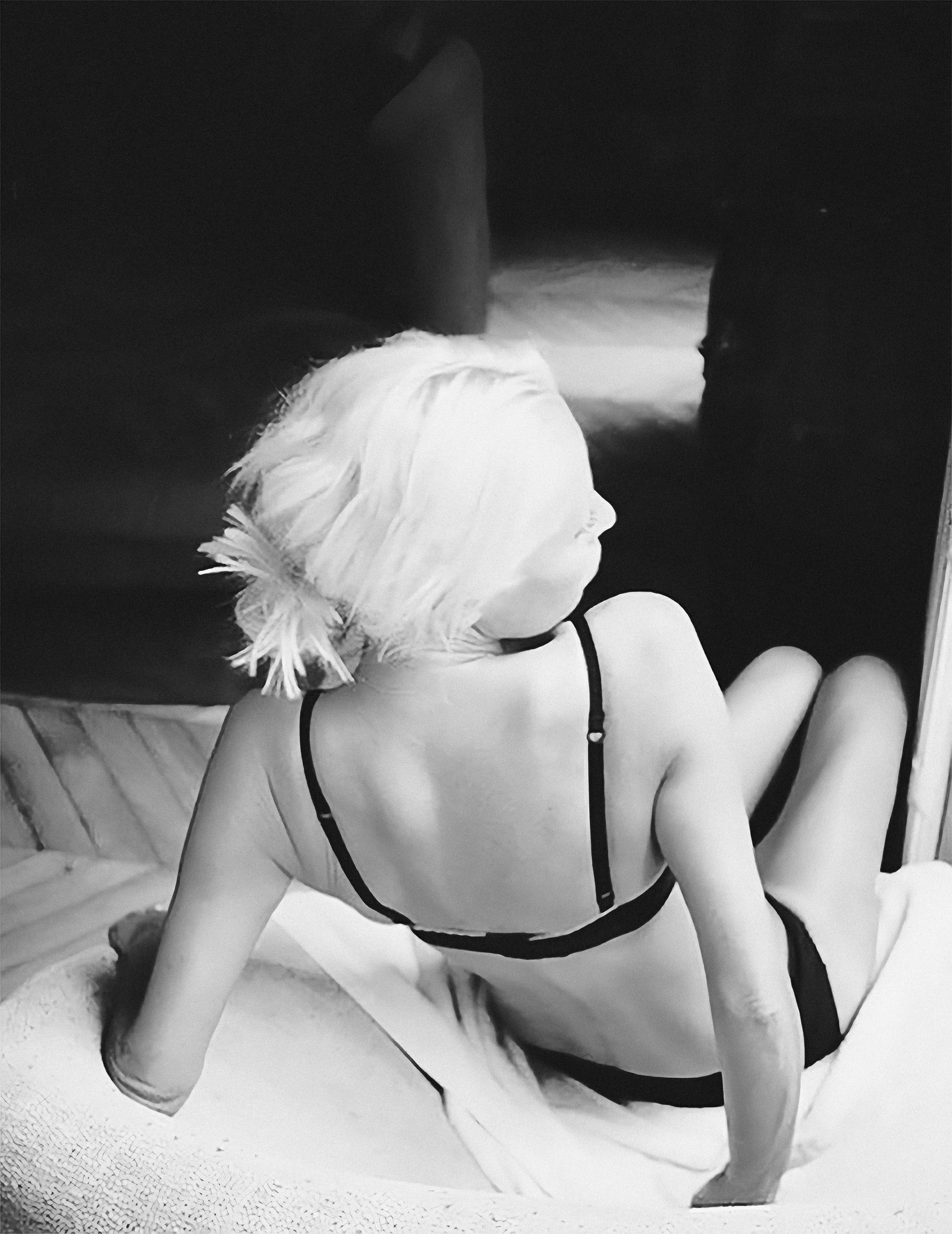

Wendy James has never played by the rules. Catapulted into the spotlight in the late '80s as the fierce and fearless frontwoman of Transvision Vamp, she became a pivotal icon of pop rock rebellion — equal parts punk provocateur, pin-up, and pop star. With her platinum-blonde hair, biting lyrics, and unapologetic attitude, James embodied a new kind of feminine power: confrontational, self-possessed, and impossible to ignore. But her story didn’t end when the charts rolled on.

Over the decades, Wendy has reinvented herself as a solo artist with a deep, restless creative drive — writing, producing, and performing music that draws on garage rock, blues, and punk, all on her own terms.

Now back with her tenth album, The Shape of History, Wendy proves once again that she’s an artist in constant evolution — unafraid to confront the past, challenge the present, and unflinchingly shape the sound of what's next. Written and produced entirely by James, the album spans 20 tracks and features an all-star lineup of collaborators, including Jim Sclavunos (Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds). With its raw guitars, poetic fury, and genre-blurring ambition, The Shape of History is her most expansive and politically-charged work to date — part memoir, part manifesto, and wholly uncompromising.

Nearly four decades on, Wendy James still refuses to be contained — and The Shape of History is the clearest declaration yet that her rebellion is far from over.

KP: When Transvision Vamp exploded onto the scene in the late ’80s, you were instantly cast as both icon and provocateur. What did that level of scrutiny teach you about fame or womanhood?

WJ: Maybe it taught me more in retrospect, as one philosophizes as they get older. At the time, I think the gift of it was that I was very young and learned fast and on my feet. You know, a dress rehearsal is good up to a point, but the live thing is always where you learn the quickest and hardest lessons of how to improve, how to perform, and how to survive. All sorts of imaginings that you have in the dress rehearsal or in your grand master plan — these things get put to rest once you're actually on the stage. So, at the time, in the center of the whirlwind, I probably just learned where cameras were and how to respond to so many questions with so much scrutiny.

Then, with the gift of age and time, you look back and realize that the way that you were handled — and any female that was in the public eye will tell you this — is somewhat different from the way that male performers were handled. I think that's still the case now, but it’s probably not as definitively sexist. At the time, also, you have to remember, I was not a female solo singer-songwriter up there all alone; I came with a gang of guys who were on stage with me and also were my best friends in life. And whilst we were in a band, the traveling tour party consisted of 30 more people that would come around in the early days to all of the shows because it was a movement. So you're insulated from whatever pontification that a male journalist at NME might have to say because you're living your life where everything's going great, basically.

And also what’s helped is the fact that as a person — whether I was 17 or 37 — my attitude has always been very ready for talent, ready for competition. I'm match fit in whatever situation you put me into. So, invariably, I met everything just completely headlong, head-on. And for a lot of the time, I think I perhaps managed to out-explain or outmaneuver a lot of the journalists at that time, who were invariably male. I can’t speak for America — but the British male perspective coming out of the ‘70s and into the ‘80s was still very backwards — women were still wives with a domestic budget, an allowance to buy the food and get the kids off to school; that was just everyday life. Of course, there have always been female entrepreneurs, there have always been female scientists, and there have always been females that have expanded the universe, but, for the most part, women were still viewed as arm candy and housewives.

This changed in punk because, of course, look at all the punk girls, look at the rock girls, the art girls, and the literature girls — whether it's Janis Joplin or Debbie Harry all the way back to Aretha Franklin and Billie Holiday, there have always been women who push the boundaries. I want to say that this was especially true for the black girls, certainly, because in those days they were singing to white audiences, which were segregated. So there have always been boundaries, and every now and then a strong woman comes along and breaks them all down. That’s what creates action for the rest of us.

So in my way, I guess, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I did my own part in the door pushing. I’ve always been like that. I remember even as a school girl — and I don't know if this is a credit to my parents or just the way that I was born — but it never once occurred to me, with the exception of heavy sports stuff like shot put or high jump, that there wasn't a single thing that I couldn’t do equally to or better than a man.

KP: I was the same exact way as a child — well, I still am! I really love that.

In a past interview with The Independent, you said, “I was the leader. I was the engine. I was never a victim.” How important was it for you to assert that kind of agency — especially as a woman in an industry that so often tries to write your narrative for you? What advice would you lend to women who struggle with finding their voice?

WJ: Well, I don't think that anyone should ever be raised to feel — or even feel within yourself for just a second — that it is a struggle. If you're feeling that it's a struggle, then you've learned some wrong lessons when you were a young girl, either from your parents, your teachers, or your environment.

I guess this connects to what I said earlier — whether I was 6 years old in a running competition or walking out on stage at a festival, it never once occurred to me that I couldn't take on and beat anyone. Now, I may be wrong or I may be right in that, but —

KP: It’s a mindset!

WJ: It's a mindset for sure. It propels you. So my advice is to be the best that you can be, and then you’ll either fail or succeed on all your own terms. Now, not everyone can be Bob Dylan, you know? [Laughs]. Not everyone can be Bob Dylan. So we're all going to get slotted into how the public finds our talents, how they warm to our talents, or appreciate our talents — and that's fine! That's our survival of the fittest. But you've got to go in with an equal mindset. If you do, then you'll be as good as you can be.

KP: That’s really great advice.

In that same interview, you said the brilliant, “Women have to prove themselves twice as much as men. And whether it’s rape victims or pop stars, women are expected to explain themselves when it should be the perpetrator explaining it.” How do you feel that double standard shaped your experiences in life, both in how you were treated, or in how you chose to respond?

WJ: I never felt that I was responsible, but I definitely can say that if a managing director of your record label makes a not-so-great decision for your band — regarding your schedule, if you’re going to do a TV show, or even taking a fucking front cover — then, of course, the press aren't going to say, “Hmm… I wonder who booked that!” They're just going to assume that it was me making the bad decision. So there definitely is that.

I didn't feel that I was being manipulated, but that’s a very, very real thing. We got so successful so quickly and in such a big way that we were already this juggernaut coming down the road that couldn't really be stopped. You couldn’t hinder us. You couldn't deviate us because we — and the public that loved us — were riding that fucking road together. There weren’t backroom boys having to artificially position me or manipulate how a female is presented to the world — I showed up the same as all of my non-famous friends at the age of 17. We came a few years after Madonna, and she had already done Desperately Seeking Susan, so we were all walking around in our ballet tutus and our bra tops and our fucking Dr. Martens. We were all out there looking like that — that was just our teenage selves anyway. It just so happened that I platformed that onto television. But that's what we would have been even if I had never done this, which is impossible. Our whole girl gang looked like that.

But seriously, I really feel for the Harvey Weinstein victims because the sexist view of things is that these women were up for it and should have never put themselves in those positions. Or, you know, that they were just using him to get up the ladder of success. Well, the casting couch is what gives permission to all of these men, anyway!

You know, we are so far superior to men. They've had us down from the beginning. We have all X chromosomes, and they have to have both an X and a Y chromosome, after all! [Laughs]. I'm joking, of course — there are many admirable and incredible men in the world. But for the typical Luddites, they would believe all of these archaic ideas of sex.

I suppose what I'm trying to say is that I have been in a position like that too, once. We were already very successful — it was my birthday, and I was treated to a very lovely dinner with a person higher up in the institution that we were signed to. And rather than congratulate me on the success that we had brought his company, by the way, or just have a jolly old talk and some good food, he put his hand under the table, grabbed my thigh, and then said something lewd. This was before our third album came out. And, of course, the person sitting there is part of the team that will decide how much money is spent on promoting our record — or they could even decide to shelve it! If I had said that he was disgusting, which would be my thought, a male ego perhaps might think, “Well, that's the end of your career!” He might go back and take revenge.

KP: Absolutely.

WJ: I don't know all of the ins and outs of reading all of the victims of Harvey Weinstein, but I do know that some of those women have said that they felt that their careers would end if they turned Weinstein down or if they spoke about the rape or sexual abuse afterwards. It does put you in an awkward position because, of course, for anyone ambitious, it goes through your mind in a split second… If I tell him to go fuck himself, is that the end of my career? It's a very real blackmail that I think a certain type of man with a certain type of power plays. They almost subconsciously do it just knowing that they have the checkbook, right? He's got the upper hand. And it’s not just women — they do this to young boys as well.

KP: I can’t speak for all of the Weinstein victims, but I am friends with a couple of them, and I know for a fact that some filed police reports before Me Too even happened, but they were dismissed. They did tell people — they were just shunned and disbelieved.

WJ: Right! Exactly! And then that opens up the broader picture — we leave showbiz behind, and we enter the world of police officers and law enforcement. Unless that's overhauled with progressive and judicial men that don't think that women were gagging for it and asked for it just because they were wearing a short skirt, then we’re not going to get anywhere.

You know, we had a case a couple of years ago in England that was just horrendous. You can research it afterwards, if you want. A girl was walking home through Battersea Park in London when a policeman called her over and said, “You shouldn't be walking in this area. What are you doing here at this time of night?” He fucking kidnapped her, raped her, and murdered her. This is a policeman — his colleagues had a nickname for him on the force as “the rapist” and hadn't reported him to their superiors for almost three years. So this girl gets strangled, raped, and murdered by a policeman. It’s just tragic. He's behind bars now, but he’s appealing his sentence.

KP: He’s appealing?! You know what? I believe it.

WJ: Yeah! And the tabloids kind of, I wouldn't say celebrated it, but it’s kind of the same thing with the weather — they love a storm. They love a hurricane. They love a disaster. And they love some gory, gory female murder. I guess it gets the clicks. And, you know, your president is a fucking sexual abuser.

KP: Oh, yeah... To say the least! I feel like we can’t even get started on that.

WJ: And whilst half the country absolutely despises him, the other half thinks that he's great!

KP: It’s abhorrent.

WJ: They'd love that golden fucking toilet, and they'd love to fucking bang all of those girls with fucking Epstein. So there's some way to go.

KP: There is definitely more than some way to go.

Much of your success — to your credit — has come from a great sense of self-confidence, both in yourself and in the band. When Transvision Vamp was first signed with EMI, you told them that you were going to be the “biggest band in the world.” Where do you feel that unflinching, uncompromising sense of self-confidence comes from? And what advice would you lend to women who find themselves crippled by self-doubt?

“If you stay in the game long enough, you can win.”

WJ: That's a really good question. For me, personally, I proudly say that I am an adopted person. And while many adopted people — you know what, I don't know; I cannot speak for anyone else. In fact, I've never even discussed this with anyone else who is adopted, but I think I always knew that life was a survival of the fittest type of thing. I've always known that unless I take care of myself, things will not be good. You come in alone, and you go out alone. I knew that I had to take care of myself from the minute that I had any kind of thoughts. It was just an instinct. I don't think that the Jameses did anything exceptional to reinforce that in me. I got some piano lessons and some singing lessons, but, for the most part, they wanted me to be a straight office worker and to find a nice husband. So it was just all my own drive. I think that the gift of me being adopted — which is also a sadness to miss out on knowing who made me, my birth parents — but nevertheless, the gift that adoption gave me was this iron rod that holds me up. It keeps me fighting.

I can only imagine that for girls who grew up in an environment that was less than encouraging, it ultimately gives you that crippling self-doubt. And I'm not talking about body shape or the fact that you want to look like a Kardashian — I’m talking about proper, deep doubt. We all say, “Oh my god, I look shit today. I really wish that I looked better. I could use to lose a couple of pounds.” If you have proper self-doubt, then I think you need to look at your environment and wonder, I love these people dearly, I really do. But are they good for me?

And that's the thing, you know? You don't get to choose the family that you're born into — for better or for worse — but you can choose who you surround yourself with as you become an adult. And as you go on through life, you should be able to develop a radar to know when people aren't good for you — shut them out and move on. Move away. It doesn't matter what they think — get them out of your life and find the people that do encourage you, that take care of you, that give you freedom, and that let you be yourself. Anything will flourish in a good environment, but if you're in a negative environment, the chances are really tough to grow yourself in a place like that. So even though you may love your parents or your boyfriend or your girlfriend dearly, if they're not helping you live the life that you want to live, then you have to just make that one simple but very difficult decision: leave them behind. You can still love them, you can still pay them respect for the things that they've given your life, but you have to leave them behind. You're still going to win or lose, but at least it will be on your own terms.

KP: I think that’s fantastic advice. We definitely make our own luck and happiness in this life.

Your image was both hyper-stylized and hyper-sexualized. What drove your interest in such powerful imagery? I imagine that you consciously reclaimed that power, but did there ever come a time that you felt trapped by it?

WJ: No, I didn’t feel that at the time. I mean, I'm trapped by it now, because I've got wrinkles, and then I didn't. You know, it doesn't matter how many filters one puts on; you're never going to look like you're 21 years old again. [Laughs]. I'm joking, of course! I don't feel trapped by it now. I feel that I look good. I'm just so happy to be alive — the alternative is far, far worse.

But at the time, no! I fucking wore it with pride. I wanted to compete on all levels, just like Mick Jagger would. I wanted to compete with music, I wanted to compete with attitude, and I wanted to fucking own it with looks as well.

I'll tell you a funny anecdote that is American. The first time I went to New York was to meet the head of CBS because, at the time, Transvision Vamp was possibly going to sign with them. They flew me to New York, and I was wearing these tiny little short, short, short, short denim shorts. And I bought these big, clunky, Marc Bolan-styled, chunky, high-heeled stacked ankle boots in black suede at a secondhand shop. In all of this, I wanted to go and pay homage to Breakfast at Tiffany's. So I was staring into the window at Tiffany's on Fifth Avenue the same exact way that Audrey Hepburn did — wistfully, with a cup of coffee in my hand. And these two American Texan women with big bouffant hair — this is the end of the ‘80s — and ankle-length fur coats… I suppose they thought they looked “classy…” Walked by me on Fifth Avenue and spat at me. They called me a tramp!

KP: [Laughs]. For Texans, that’s very New York.

WJ: Well, the women walked to the end of the block, and I thought, Okay, I have to get to my next meeting now. So I knocked on the window of a yellow cab, but I didn't really understand cabs at the time. I didn't know that his light was off, which meant that he was eating his sandwich on a break. Anyway, he wound down the window — and you can see how long ago this was because he had to physically wind it down — and he shouted, “Fuck off!” And so within thirty seconds flat, I had been called a tramp and also had been told to fuck off. And I just remember basking in it, saying, “I love America. I love New York.” It was just what I needed New York to be.

KP: [Laughs]. I love it. You lived in New York, right?

WJ: Yeah, I'm a big New Yorker. I moved there in 2002, and I left in 2016.

KP: Wow! Okay, cool.

WJ: Yeah, New York is my domiciled home. I mean, I love it. I know every back street just as I would London. But back to the ladies from Texas!

KP: Okay, yeah. Back to them! [Laughs].

WJ: They called me a tramp because I was wearing short shorts and high-heeled boots, but they're in floor-length dead animals and bouffant hair — probably all paid for by their hedge fund, crappy husbands. And they called me a tramp?! I think, god, it might be the other way around...

KP: Yeah, I think so too. [Laughs].

WJ: Nevertheless, it was a great welcome to New York. And it made me move there.

KP: Yeah, very quintessential. I'm so happy that the city was able to give you that welcome.

But back to Transvision — do you feel that the band was misunderstood in its time, especially by critics? What do you feel is a misconception about yourself that still stands today?

WJ: Oh, well, in those days — I don't think it's the case anymore, particularly — but the press had an awful word for women, which was “bimbo.” Did you ever hear of that word?

KP: Yeah.

WJ: So because I was blonde and I did actually have substantive answers to give, rather than just coy, submissive female answers where I’d appear subordinate to men — anyway, whatever, we've belabored that point — but because of that, their verbal violence toward me was to try and label me a “bimbo,” along with anyone else who was blonde. It's just another sexist ploy.

So if there was any misconception then — which I think I've outlived now and changed the course of by making all my own albums, writing all of my own lyrics and music, raising all my own money, running the entire business, and still having it be on an upward trajectory all these years later — I’ve surely shaken that word loose now. It kind of got dissipated into the 90s, but at the time, I think the quality of some of the songs was definitely diminished by them wanting to attack me, trying to make me out to be some dumb blonde.

But again, I've outlasted how many managing directors? How many of those male journalists that wrote for NME? They thought that they were hot fucking shit, and now they’re just middle-aged, bald blokes with beer guts. If you stay in the game long enough, you can win.

“But that’s what rock and roll is, right? Our job is to be the outcasts of society.”

KP: That’s one of my favorite beliefs. Never, ever say die.

The band broke so many boundaries in terms of image and sound, as did you as its frontwoman. What was the most radical or subversive thing you think you did during the Transvision Vamp years that people didn’t recognize as such, either then or now?

WJ: Well, I've been probably just a tiny part of the very rich history of women who opened up the horizons just a little bit more. Now, if you look at a 14-year-old girl, half of these things that I'm imbued with because of the experiences that I had don’t even enter her mind! They're equal, and they can do whatever the fuck they want. That's because all of us had been chipping away — and, in turn, they will chip away for the next lot.

We made great, great songs. We were the soundtrack to a generation, and we have lasted in terms of how people enjoy the music. I was a strong, independent, intelligent, beautiful female that pushed the door down just a tiny bit more for the next girl. And that happened way back from women suffragettes all the way to Tina Turner. Somebody like her completely changed the world with her stage presence — and she was surviving domestic abuse, which she escaped, segregation, and extreme racism in the process.

We all come with our own story, and you’ve got to do the best that you can do with it.

KP: We absolutely do.

You’ve often spoken about bodily autonomy and performance — how has your relationship with your body evolved over time, especially in the public eye? What kind of resistance did you face from the industry for refusing to “grow up” in a traditional, demure, palatable way?

WJ: Well, here's another funny story. When we were filming the video for “I Want Your Love,” I was wearing a skin-tight pink dress made of really unforgiving material — you can go back and look. I wasn't as thin then as I became in later life and as I am now — I still had my little teenage curves. And the video director asked very discreetly, but concerned, to the manager, “Is she pregnant?” All because I had a little fucking belly on me!

But speaking of the present-day, well, I'm older now. So for me now, the requirement is for everything to still be in proportion and for me to be fit.

Compared to back then, we've got different role models now. I see far more bootylicious girls now, far more curvy girls being role models and heroines compared to the days when I came up. Back then, they were the years of the ‘80s and ‘90s supermodels. Unless you were naturally born like an alien, six-foot-two and absolutely, gorgeously perfect… We mere mortals simply can't do it! I suppose then I was aspiring to try and look as good as them, whereas nowadays, you can pick your own body type to be your example. Even in pop stardom, whether it's Sabrina Carpenter or Missy Elliott, there are all sorts for everyone these days. I guess there always was to some extent, but back then there was Debbie Harry, there was me — there did seem to be this more typical version of beauty. And in the days that I grew up, you had to be Nico or Anita Pallenberg — it was all a type. Now we have so much more room for freedom and expression.

KP: That’s certainly true.

While most of your work was shocking or, at the very least, attention-grabbing, it never felt forced or like a ploy for attention. How did you manage to walk the line so well between shock value and artistic truth?

WJ: I didn't find it shocking! Like I said earlier, my girlfriends and I were already dressing like that, right? Just like the punks went and bought their fashion from Vivienne Westwood, we all had our looks. And Madonna gave birth to a lot of what was going on when I was a young teenager. You just think that you look like the bee's knees and everyone else is really straight and boring, right? So it was them that got shocked — to us, it was never shocking. And that’s especially true today. When I see all sorts of people in the street, in the cities — young people, I mean — they don't care if you're shocked… That's your problem, right? They just think that they look the best they can look. The shock is always on the side of the receiver. I guess that there are some people that go out of their way to shock…

KP: Yeah, and I think you can tell! When I look at you, it never looks forced.

WJ: I get that! And that's probably the slight differentiation between rock and roll and pop, right? You know, the New York Dolls all walking down St. Mark's Place in their high-heeled cross-dressing goodness in the ‘70s, I'm sure all the old bags on St. Mark's went, “Oh, what is he doing? Who are they?” But that’s what rock and roll is, right? Our job is to be the outcasts of society. In pop music, it's supposed to be inclusive entertainment — a sugared cherry on top for consumers. It's a very different paradigm. You can manipulate pop far more than rock. Rock and rollers fell out of bed and probably need a cigarette and a drink to keep going. [Laughs]. That's just how it presents.

KP: [Laughs]. Right, right. There is always an unmistakable genuineness.

And to move on to your solo work! You released your latest solo album, The Shape of History, just last year. What has your solo work taught you about yourself that your work in a band couldn’t, and do you have a favorite track off the album?

WJ: That's a good question. Well, I've written everything and produced everything, but, of course, I'm not working in a vacuum. I am co-working with my team of musicians, and they’ve all been working with me now for 7, 8, 9, or 10 years.

I mean, I do actually think that I write really good songs.

KP: You do!

WJ: And I may be at number 300 in the charts or number 3 — and it really, really will make a difference in my life in many ways, of course — but it will not make any difference to me regarding whether I think the song is good or not. So I do carry myself through the world now with that knowledge, which I didn't have in Transvision Vamp. I knew that I was a good entertainer. I knew that I was a natural on stage. If you put me on stage, I could sing and dance, but now that I've written all of these songs, I’ve learned so much about how music should be produced. If you were in the studio with me when I produce them, you’d see that the minuscule micro-attention to detail and obsessive perfectionist streak that's in me has led me to learn so much more. I don't necessarily write the most obvious three-chord riff now — I look for ways to expand the song and make it more unique.

And after all of this, I carry myself now knowing that I am really good at what I do, so that kind of makes you impervious. I've seen so many musical engineers who come to the interview at the beginning of the album looking for the job, and they say, “Oh, don't worry! I can do 18 hours a day, and you won't have to worry about a thing!” But I catch everything. It’s a gift. This is all a dream come true for them, but after two weeks, they're run ragged.

And I don't want this, but I can only imagine it's with that same kind of self-assurance and obsessiveness that Stanley Kubrick made his movies. The correct word is “auteur,” where you write it, you produce it, you mix it, you master it, you do the artwork, you do the interviews… And then, finally, you do the performances. It’s all you.

Ultimately, there are many, many things in life that I am not good at — like electrical work or tiling! [Laughs]. But making music? I know that’s my thing.

KP: It definitely is.

What advice would you lend women about life, work, or love?

WJ: Don’t be dependent on others. Don’t be codependent, where you get into a toxic relationship and one minute it might be the most fantastic love you’ve ever had, but then that person might turn on you and make you feel so devastated to the point of being unable to carry on. The high is just not worth the low. You've got to learn how to walk away. You've got to learn how to leave a negative job, a negative man, a negative woman, a negative family, a negative situation, a negative country!

Sometimes you stand a much better chance of just leaving it all behind and starting somewhere else. I did that when I left London! At that time, obviously, I had some money from Transvision Vamp. I owned a house and all the furniture that goes with it, and I got rid of all of it. When I moved to New York, I moved with one suitcase, one book, and one CD — Bringing It All Back Home by Bob Dylan and a collection of journalism called The New Journalism by Tom Wolfe. I had a Prada skirt, a big thick jumper, and a pair of walking boots. I moved one week before Christmas, so it was cold there. I had to pound the streets looking for a little flat, and then somehow I got cable hooked up in time for Christmas Day. I owned nothing, but I had gotten a bed from wearemattress.com or whatever and a big TV from a shop on Union Square. I got the cable hooked up, and by Christmas Day, I was lying in bed flipping through all of the American channels. It was just so great.

I would urge women to travel by themselves. Yes, there can be scary situations, but we know that we're cognitive travelers — it's never a scare unless you find yourself in an unfortunate situation. You know, there's something so refreshing about traveling by yourself. You sit at a bar or in a café — you get a croissant, a cup of tea, you meet people, and, of course, you see things that you would never necessarily see if you were traveling in the company of others. It's never as scary to leave as it is to stay.

KP: I love that. I think that’s great advice.

What would you tell your younger self?

WJ: Invest your money and don't sell your house. [Laughs]. It's purely pragmatic. I have no lessons on how to be better because I was as good as I thought I could be at that time. But I blew through money. And then I sold that house to move to New York, but if I'd kept it, I could still be living off of that rent money.

When you're young, you just say, “Fuck it, the best is ahead of me.” And you should! But be pragmatic as well.

KP: That’s your toughest advice to follow. [Laughs].

What do you feel makes a provocative woman?

WJ: Whether it's Ingrid Bergman, Patti Smith, Ursula von der Leyen, Fiona Hill, or Anne Applebaum, these women are provocative to me because they make me want to get off my fat ass and work harder. It's not boobs out — it's the will of the female to use all of her intellectual powers to not be put down by anything. That's always what liberates me and provokes me to move forward.