Deb Googe on Punk, My Bloody Valentine, and Courageously Walking Away from Success

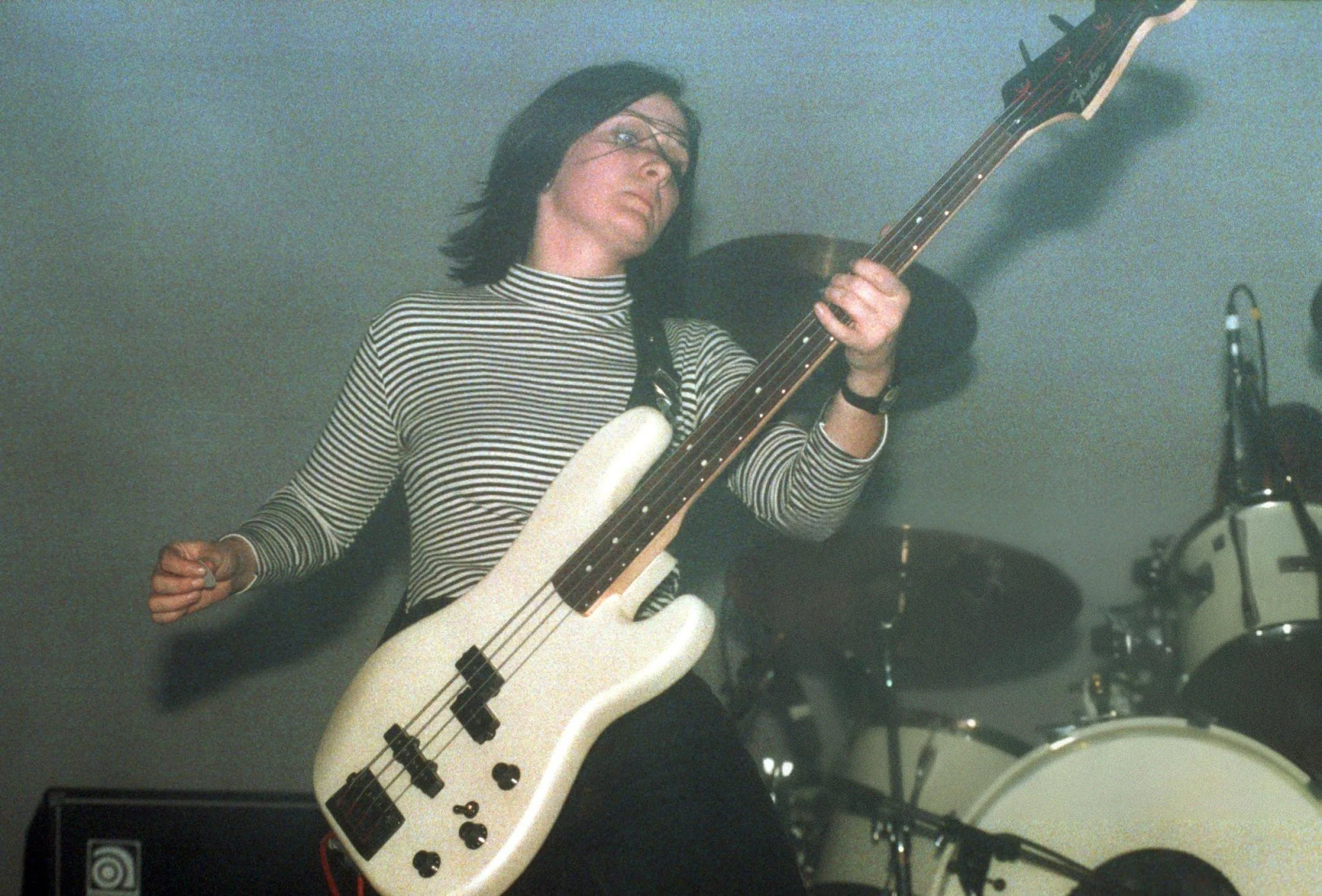

From her blistering anarcho-punk beginnings to crafting some of shoegaze’s most iconic basslines, Deb Googe has carved a fiercely original path through four uncompromising decades of alternative music.

Emerging from the vibrant underground music scene of the 1980s, Googe's journey began with her involvement in the anarcho-punk band, Bikini Mutants. In 1985, she joined My Bloody Valentine, contributing to the band's seminal albums Isn't Anything (1988) and Loveless (1991), which are often cited as cornerstones of the shoegaze movement.

Following her departure from My Bloody Valentine in 1996, Googe briefly worked as a taxi driver before forming Snowpony in 1997, a project that blended elements of indie rock and experimental sounds. She also collaborated with Primal Scream in 2012 and Thurston Moore's solo project in 2014, later contributing to albums such as The Best Day and By the Fire.

In 2023, Googe embarked on a new musical endeavor under the moniker da Googie, releasing a split 12" record that featured her solo tracks alongside the duo Too Many Things. The release — which included “Slither,” “Pipe Dreams,” and “November New” — marked a significant step in Googe’s artistic evolution, spotlighting both her undying relevance and her emblematic spirit of experimentation.

In 2025, she returned with The Golden Thread, a collaborative album with pianist Cara Tivey, released via Tiny Global Productions — a project that not only continues her lifelong pursuit of sonic exploration, but reaffirms her place at the forefront of boundary-defying music.

KP: Lately, as I’ve been preparing for these Noir conversations, I’ve noticed that my research often intersects with thoughts that I’ve been recently sitting with.

I came to the realization lately that some of my favorite cultural heroes — some of the women that I think are the coolest — totally abandoned their careers at their heights to either pursue something that was more of interest to them or to rediscover their inner happiness. And I could include you in that same list.

While I was reading an interview that you completed with Creation Records, you said that you left My Bloody Valentine because you “hadn’t been happy for a long time and [you] couldn’t see any way out of the situation.” I think it takes a massive amount of courage and self-mastery to walk away from undeniable success, and I applaud you for that decision.

What was your headspace like at the time, and was there a specific moment that led to that decision? I know that so many women feel very stuck in their lives or their careers, so what advice would you offer them about reclaiming their joy and their freedom?

DG: I don’t think that it was one single event. I think that it had just been building for a long, long time — gradually, slowly.

As a band, we weren’t completely off the rails, but things weren’t great. After we came back from the Loveless tour, we got an advance from Island Records and used it to build a studio. We basically all lived there together, and over time, we just became pretty dysfunctional.

It wasn't like I had a sudden lightbulb moment where I thought, I have to leave right now. But things had been shifting. I’d already started physically leaving the house more often. We were all usually in the house together most of the time, but on this particular day, I had gone out to drop off a tape to Island Records, which was on the other side of London. I just remember, on the drive back from Island to the studio, I suddenly decided that I didn’t want to go back.

So yes, there was a specific moment — I suppose there always is — but it wasn’t like this dramatic I'm free! type of realization. It had been a long time coming.

That day, the traffic in London was awful — total gridlock. I nearly missed Island before they closed. Everything just felt so chaotic. And in a way, I think that chaos mirrored where we were at as a band — all over the place. Colm [Ó Cíosóig] had left a few months earlier, other things had happened, and I think it just all added up. Being out of the house gave me a little perspective. The idea of returning didn’t exactly fill me with joy, and at some point, I just thought, I’m not going back.

I had a flat and I had a girlfriend, but I barely saw her. That life — the one outside of the band — I was hardly connected to it anymore. I think I just realized that I needed to touch base with the rest of the world again.

So no, it wasn’t one clear moment. It was a buildup of many things.

And as for advice, I don’t really have any great advice, honestly. It's easy to tell someone to leave a relationship, or a job, or whatever, but ultimately, it has to be their decision. In my experience, especially with relationships, when someone tells you, “You should leave them…” — even if it’s the right thing to do — most people end up going back. It’s rarely helpful. But you can encourage people, let them know that things might get better, and they probably will.

For me, I felt incredibly elated after I made the decision to leave. But two weeks later, I felt completely lost. It wasn’t just leaving a job. My identity had been wrapped up in My Bloody Valentine for a decade. So I suddenly didn’t know who I was anymore or what I was supposed to do. At first, I was happy. Then I crashed. For a long, long time, I wasn’t sure if I had made the right decision. But ultimately, you find your way. You’ll be alright. And that’s really all that you can tell someone: whatever the decision is, trust that it’s for the best. You’ll always find your footing again.

KP: You always do. In that same interview, you described cab driving as something that you “quite liked” for a time — especially with the late-night energy of Soho’s queer nightlife.

DG: I actually did that when I was in My Bloody Valentine, too! [Laughs].

KP: What?! Did you really?

DG: Yeah, I really did for a little bit here and there!

KP: I love that; that’s so amazing. Well, in the interview, you mentioned picking Miki [Berenyi, of Lush] up one night, which made me laugh quite a bit — it’s such a small world! I just spoke to her a few months ago; she’s the best.

DG: Well, you know her; she got in the back of the cab and was like, “Debbie?! What the fuck are you doing?! I’m driving you. Where would you like to go?” [Laughs].

KP: Oh my god, that’s genuinely incredible. That might have been the most iconic cab ever. [Laughs].

But sometimes the work that we pick up out of need, boredom, or simply seeking something completely different can teach us a lot about ourselves or, ironically, our most core passion.

Looking back, did that experience offer you any unexpected perspective, either creatively or personally? And do you ever miss the anonymity or the odd intimacy of that kind of job?

DG: I mean, I learned a lot about London. [Laughs].

I’ve got the world’s worst sense of direction, but I ended up learning how the city connected all over, which was actually really lovely.

I drove overnight, always on the late shift, because I was usually picking people up from gay clubs. It was a lesbian and gay cab company. I mean, you didn’t have to prove your credentials to get in… [Laughs]. But we mostly picked up outside of gay bars, clubs — that sort of thing. Everyone in the office was gay.

I guess one thing I learned about myself is that I’m very adaptable. I probably always knew that to some degree, but this really confirmed it. I adapted to that situation quickly, and I actually really enjoyed it.

And the wild part is, I had only passed my driving test about two weeks before I got the job.

KP: There’s no way. [Laughs].

DG: Oh, yeah! I just happened to be strolling past and saw a job opening advertised in the window. I thought, I’ll do that. It was very brave — or reckless, maybe. Honestly, it was kind of mental that they hired me. [Laughs].

The interview questions were a bit unconventional. Because it was a lesbian and gay cab company, they didn’t really ask the usual things. They never asked how long I’d had my license — just whether I had one. I mean, I did — but barely.

What they did ask were questions like, “How would you get from such-and-such gay pub to St. Mary’s Hospital?” which was the main HIV hospital at the time. And I knew those places because I lived in London and I was gay — I had been to all of them.

Even though I hadn’t driven much, I had cycled all over the city for years, so I knew rough routes. I could say, “Oh, I’d go along that road to get to that one,” or if they asked where The Bell was, I’d say, “King’s Cross.” So I had a sense of the geography, just not the driving part. [Laughs].

KP: Well, that part’s not important! [Laughs].

DG: And to make it even more ridiculous, I had a terrible car. I liked it — it was vintage — but it was always breaking down and totally unsuitable for cabbing. So I had to rent a car.

I made absolutely no money. I’m a terrible businessperson. Between the car hire, the extra insurance, the fee, petrol — it all added up. Plus, I was constantly getting lost because of my awful sense of direction.

Jobs would take me ten times longer than they should have. Anytime I could, I’d head for the river — at least then I knew which direction I was going. If the river was on my left, I was heading west. If it was on my right, I was going east. That was about the extent of my navigation. Everything else was a bit of a gamble, really.

But yeah — I learned that I’m adaptable, and I’m very open to experience.

KP: That’s one of the greatest stories I’ve ever heard on here, wow. [Laughs]. I really love it.

To turn to the music, you started playing the bass at a time when many women simply weren’t. I’m curious as to what drew you to that particular instrument in the first place and what your earliest experiences with music were like, on either a personal or professional level.

DG: Well, first of all, I formed a little band at school. It was part of a school project, and there were four of us: me, my friend Karen, Joanne, and a girl called Alise.

Karen was kind of the leader. Her brother played guitar, so she had access to one, and she just declared, “I’m playing guitar, and you’ll play bass.” I didn’t have a bass. Then she told Jo, “You’ll play the drums,” and she didn’t have any either. I guess Alise must have been the singer, but honestly, none of us had any instruments.

Still, from that point on, it kind of got into my head that I was going to be the bass player. That band never actually did anything — it was just a school thing — but I kept going with it. Karen and I kept playing together, and my next-door neighbor Rose joined in as the singer.

Eventually, I did get a bass. My mum and dad bought me one as a joint birthday and Christmas present. It was from Woolworths — literally the cheapest bass that you could get at the time. But I loved it. I remember taking it to bed and sleeping with it for the first couple of weeks. It just felt so precious.

KP: Aw, I love that! Did you have an amp at that point?

DG: No, I didn’t. I don’t even remember when I got my first amp. I don’t think I had one for years.

KP: Really!? So you were just playing the bass acoustically?

DG: Yeah, just playing it unplugged. I think we practiced at Karen’s house a lot, and her brother — the guitarist — had amps, so we’d use his setup. At home, I’d just work things out quietly, acoustically. It wasn’t an acoustic bass or anything, so it was very soft, but that’s how I practiced.

I think I only got my own amp when I joined my first proper band, which was an anarcho-punk group called Bikini Mutants. I don’t even remember where the amp came from or where I kept it, but we definitely had one.

We used to rehearse at my friend Gem’s place — she had this space where a bunch of little anarcho-punks would hang out. We were all in bands, and there was just a load of communal gear there. It probably wasn’t even my amp, to be honest — it was just part of the mix of stuff that everyone used.

KP: Whenever I speak to members of such iconic bands, I’m so curious as to whether they felt this cultural shift occurring as they played in real time. In the early MBV days, how aware were you that you were helping shape something sonically radical — or did it feel more chaotic than conscious?

DG: For me, anyway, I wasn’t aware of it at all. I just sort of went bumbling along, really. Things just happened.

Like I just said earlier, the first band that I was in was an anarcho-punk band, and that was definitely chaotic — but knowingly chaotic. We were known as the best bad music band in Somerset, which, I have to tell you, is a very small part of the world. We really cornered that tiny little niche. [Laughs]. We thought that we were doing something radical — mostly because we were noisy and political. Back then, we considered ourselves anarchists and all of that.

As for My Bloody Valentine, I just sort of joined the band, and things evolved from there. The My Bloody Valentine that most people know now is really different from the band that I originally joined. When I joined, Bilinda wasn’t even in it. The singer was this guy called Dave [Conway], and our sound was much more garage-y — influenced by bands like The Cramps and The Birthday Party. Much more raw, more chaotic. And Dave was a real frontperson — totally in your face. He’d throw himself on the floor and roll around — really wild. Quite the opposite of Kevin [Shields] and Bilinda [Butcher]. So the band evolved; the sound evolved.

You’d have to ask Kevin whether he always knew where it was going. I don’t think so. I think these things just tend to take shape over time. As you get older and play more, you start to develop your own style. You figure out what you like and what you don’t.

But no, I don’t think that there was an agenda from the start. We just wanted to play gigs and put some records out, really.

“You have to stay determined. You have to fight to get those rights back again. There’s this horrible wave going through the world at the moment. I just really hope that it’s only a wave — and waves always pass.”

KP: Usually that’s how the best things come. You’ve spoken about your upbringing as “punk through and through… I came up through punk and the ethos, and knew strong women.” How do you feel that combination of ethics and influence shaped your experience as both a woman and a musician? Do you feel like it gave you any sense of armor in dealing with everything that you did in the music industry moving forward?

DG: Yeah, I think it’s a bit of a weird shift, isn’t it? When I was about 15 or 16, that’s when the punk thing really hit where I was. If you were lucky enough to be in London, it might have looked a little different — but by 1977, it had definitely become a national thing. And by the time I got involved in that first band, the anarcho-punk scene really shaped everything that I did in those formative music years. It’s still with me. I still have lots of friends from that time, I still see a lot of those people, and I still really believe in a lot of the values that we held back then.

I’ve always felt that music, art — most things, really — are better when they’re independently funded. There’s something much more interesting about it. Once big business gets involved, it tends to flatten things out; it makes everything feel a bit homogenized. I’ve always thought that. I probably always will.

Also, growing up seeing people like Siouxsie Sioux, The Raincoats, and a great band called the Poison Girls — that had a huge impact on me. Poison Girls especially, because Vi Subversa — who fronted the band — was in her mid-40s when I was about 16 or 17. At the time, that felt ancient to me. I mean, now of course, I think, God, that’s nothing! But back then, it was absolutely radical.

Apart from mainstream icons like Shirley Bassey or someone like that, I had never seen a middle-aged woman leading a punk band — especially not an anarcho-punk band. Vi was full-on: screaming, powerful, and absolutely owning the stage.

And she had completely changed her life, too. That was so inspiring to me — to see someone that age stepping into something so raw and political and doing it without apology.

Yeah, it had a massive effect on me. Absolutely.

KP: On the topic of punk, I go back and forth between whether I truly feel that the music industry today — or even culture today — can breed that same punk ethos when everyone is either controlled by suits or their work’s marketing relies on following an algorithm that some corporate machine dictates.

Do you think the kind of strength you saw in those early punk women is still visible in today’s music scene — or has it evolved into something else?

DG: I mean, I definitely think it’s different — but everything’s different, right? Things evolve. They turn into other things.

And with the Internet — yeah, you’re right. A lot of things do get boiled down to algorithms now. But I also think there’s a whole generation of people who’ve grown up knowing how to sidestep that a little bit — or at least play along with it and work it to their advantage.

There’s a whole new kind of anarchy happening — a sort of digital anarchy — and I think it’s really exciting. It’s cheap, it’s accessible to most people if they want it to be, and that space is full of possibility.

Of course, corporatization is still everywhere. It’s global, and it’s massive — and there’s probably more money for people who already have money than ever before. The divide is still there, and it’s awful, and there doesn’t seem to be a clear way out of that.

But I do think the internet has, in some ways, genuinely unsettled a lot of corporate power structures. It’s put the shits up a lot of big companies, I think — because they’re a few steps behind a lot of the time. And that’s really interesting.

So yeah, things have changed. And I’m hopeful — even if I don’t know half of what’s going on. I’m an old woman! But I like to think that there’s loads of interesting stuff still happening out there that I have no clue about. That’s my hope.

I’m not even on TikTok — and to young people, that’s already last decade’s news!

So yeah, I still think there’s still space for all kinds of things to be going on. And I really hope that they are. Well, fingers crossed.

KP: Fingers crossed for sure! You’ve said that you don’t read music and don’t really practice —

DG: Well, I don’t practice daily, but I do practice when I have to.

KP: Okay, well that’s a relief! [Laughs]. But how do you think that relatively intuitive approach to music has shaped your unique skills as a musician? What advice would you lend women who want to sharpen their own?

DG: I don’t read music. I try to, every now and then. I’ve taken a few classical piano courses thinking, If I sing or play classical piano, I won’t be able to rely on memory alone, because I can't just remember everything — it's too complex. So I thought that I’d be forced to read, but very quickly, I’d just start listening again, half-remembering, half-guessing. And then I’d go off on tour and miss a bunch of classes. So, I don’t know — I kind of wish that I could read music. I wish I’d learned when I was younger, but I just never bothered. And now it feels like it’s too late.

I do practice — especially when I’ve got something coming up. I’ve got a gig with Thurston [Moore, of Sonic Youth] next week, so I’ve been running through songs, just to get them back in my head. They don’t all just stay there.

Then after that, I’ll have to switch gears for MBV — we’re going out again towards the end of the year. We’ll probably start getting together next month to figure out what’s going on there. So yeah, we’ll practice for sure.

But it’s not like I sit down every day and think, I need to practice bass today. Especially now. When I was younger, you just played. It wasn’t “practicing” — you got together with your mates, you were doing gigs, and you just played all the time. I didn’t sit down and do scales or anything like that. Maybe I did at some point, but I honestly can’t remember.

These days, even when I’m working on music, it doesn’t always mean playing guitar. I might be editing or mixing or doing something else if it’s for one of my own projects. And sometimes I’m just making noise without knowing what I’m really doing — but I’m often doing something with music.

That said — I’m literally sitting here right now, looking at two basses in front of me because I’ve been working out parts for Thurston’s set. So yes — I practice when I need to; it’s just not daily.

“Whatever the decision is, trust that it’s for the best. You’ll always find your footing again.”

KP: That’s not needed! I started playing guitar when I was around six, but when I was really young, I was classically trained as a pianist. And you’re right — there’s something about classical piano that really sticks with you.

Once I started playing guitar, the piano kind of left my brain in a way, but even now, 20 years later or whatever it is, I could still sit down and play my scales. There’s a lot of muscle memory in piano for some reason.

And I was never even a great sheet music reader, which is unusual for someone who was classically trained. I’d just learn everything by muscle memory. I’d play it a couple of times and then somehow be able to repeat it. But I do wish that I were better at reading music. It’s something that I never quite mastered, and I regret that. I still kind of want to learn one day.

DG: Yeah, I’d love to as well. I think that reading music feels like this magic language. I’d love to be able to just look at a piece of sheet music and — not play it perfectly, obviously — but at least be in the right ballpark. To me, that’s magic — that someone can just hand you a page and you’re able to make something from it right away. But I don’t think it’s ever going to happen for me.

KP: No, come on! You can do it. To go back to punk for a moment, it was often the experience of female performers that the punk and post-punk scenes were often progressive politically but still sexist in practice. Did you experience that contradiction?

DG: I think I was quite lucky, actually. My initial foray into playing music was through the anarcho scene. The first band that I was in had a rotating lineup, but there were always at least two or three women in the group at any given time.

The gigs that we played — we usually put them on ourselves. It was a very DIY setup. Our group of friends also ran a little fanzine and a label, so we had this sort of collective going, made up of both men and women.

That was my first real experience in music. And in that context, there was no real hierarchy. We were all friends, and when you play in bands, you tend to become like a gang — in the best sense of the word. It gives you this natural support system, regardless of gender. So I was very lucky to start out that way.

Later on, with My Bloody Valentine, it was two women and two guys. And to be honest, Kevin and Colm weren’t exactly the most macho men either. [Laughs]. But all of us were more than capable of standing our ground. We’re not the in-your-face type — we’re all pretty laid-back — but we all know how to hold our own.

We also usually had other women on tour with us — whether it was the tour manager, merch person, or, later on, monitor engineers. So we’ve always had a pretty mixed team around us, which I think helped.

That said, I know lots and lots of other women who’ve had very different experiences — and not great ones. I just think, for me personally, I’ve been quite lucky.

It might also be an attitude thing. I think people pick up on energy pretty quickly. I’ve got a bit of a resting bitch face — and very cold blue eyes — so I think sometimes people are just like, “Okay, not messing with her.” [Laughs].

KP: That’s definitely a thing; I think about energy in that way a lot. But that’s so interesting. When I speak with women, it’s often either “I experienced that every single day” or “I never experienced it at all.” Interestingly enough, there’s rarely an in-between, which is why I love asking. The answers are always so different.

DG: Yeah, and it’s not like I haven’t experienced anything. In the music world, people do treat you like an idiot sometimes. You really do get mansplained a lot. But I’ve also seen people treat Kevin like an idiot — and Kevin’s far from an idiot, especially when it comes to sound. So sometimes it’s just part of the territory.

Honestly, men get mansplained to, too. There are just some people out there — usually jaded, usually not nearly as knowledgeable as they think — who just love the sound of their own voice. They don’t really care whether you’re a man or a woman. They still think they’re the smartest person in the room.

KP: That’s very true. And on the topic of identity and belonging, did being visibly queer ever feel like a form of quiet activism, even when you weren’t being overtly political?

DG: Yeah, I think so. Certainly in the ’80s… I mean, part of the reason that I left Somerset was because being gay in Somerset in the late ’70s and early ’80s just didn’t feel like an option.

Moving to London was really liberating. It was the first time that I realized there were actually other gay people out there. Up until then, it felt like there were only two of us — me, and the woman that I first fell in love with. That was it.

So yes, London was freeing. But it was still a hostile place in a lot of ways. In fact, I’d say that I’ve had more aggression aimed at me for being gay than for being a woman — at least in London.

It wasn’t always physical — though there were a couple of instances — but mostly it was verbal, people shouting at you in the street. That kind of thing. It doesn’t happen as much these days, but occasionally it still does. When I first moved to London, though, it was happening all the time. And back in Somerset? That was its own kind of strange. Most people there didn’t even acknowledge that lesbians existed. It just wasn’t part of their framework. So, in a way, you didn’t get insulted because they couldn’t compute it. But if they had acknowledged it, you probably would’ve gotten your head kicked in. It was just that kind of place.

In London, there was at least a bit more awareness, but still loads of ignorance — especially in the early ’80s. And on top of that, there was also this huge fear of feminism. You know, if you had short hair — which I did, or I eventually did — you’d get pegged as this scary, radical feminist. And that wasn’t a particularly popular identity back then either.

So yeah, it was a double whammy sometimes. But mostly it was just insults. And honestly, I don’t really care what strangers think. I’m never going to see them again. They can shout all they want — I just don’t want to be hit. The idea of any kind of violence or fighting really terrifies me. But shouting? It’s scary, sure, but you just move on.

KP: That’s really powerful to hear. I’m gay myself, and when I was growing up — I was born in ’93 — it still wasn’t okay to be out, especially in school. This was the early 2000s in New York, and it’s been heartening to see things start to shift, but of course, there's still a long way to go. Especially with the current administration here in the US. Needless to say, it’s not great.

DG: Yeah. It’s hard to even know what’s going on sometimes — there’s so much chaos. And it’s not just there. Here in the UK, too, the whole conversation around trans rights is horrific right now. Some of the laws that have recently been passed — or even proposed — are so bloody archaic.

It just reminds you how quickly the progress that you think you’ve made can be stripped away. But you have to stay determined. You have to fight to get those rights back again. There’s this horrible wave going through the world at the moment. I just really hope that it’s only a wave — and waves always pass.

KP: Me too. Though I don’t think it can pass soon enough.

After being in bands, you went on to create your own solo project, da Googie. What did branching out on your own — without the usual collaborative push and pull — teach you about music, your instincts, or even how you personally related to sound and structure?

DG: That's a big question. I guess what I learned about myself is that you can just do things.

You can think about something for years — not act on it — and then one day, you just do it. And people aren’t there to shoot you down! Well, some people are. But it’s kind of like being shouted at on the street — you can ignore them.

Most people aren’t trying to cut you down. Most people are genuinely kind. They’re interested, and they want to encourage you. I’ve had a lot of encouragement. I don’t think that I would’ve done it without that.

It was actually Jem [Doulton] — the drummer who plays with Thurston — who got me to do my first solo thing. I don’t know why I just pointed over there like that; he’s not in the room. [Laughs].

He put on a night at Servant Jazz Quarters in Dalston, which is a really small venue. There was a headliner, and then Jem and John — who does electronics with Thurston — were going to do an improv set. And Jem was like, “We need one more act.” John said, “You should get Deb to make some noise.” And Jem went, “Yeah, Deb! Come make some noise.” So I said, “Sure, I’ll come make some noise.” But I was joking. I was actually drunk at the time, so I was really joking. [Laughs]. But Jem — bless him — is a doer. He doesn’t just say things. He really follows through. And I kind of forgot that about him. So two weeks later, he sent me a poster and asked, “Is this how you want your name to appear?” And I was like, Oh my god. I’m actually doing this. There was a moment where I thought, Well, maybe I could still get out of it. But then part of me said, Just do it. What’s the harm? So I did it.

I couldn’t quite face the full-on improvisation though — I’m not an experienced improviser like Thurston is. He loves improv. I think he might love it more than anything else. But being around him really helped me gain the confidence to try. I’d never improvised with anyone before I did with him. And that opened me up.

For that first show, I used loops — I had been playing around with loopers in the studio for years. So I pulled together bits I had, layered things, made noise, and built structures. That was it. And from there, I started developing more structured songs, and during lockdown, I wrote a couple. So that first record — the split 12-inch with Jem’s band, Too Many Things — was a mix of loop-based stuff and one song that I wrote during lockdown. There were three tracks on my side. That was the first da Googie release.

KP: That’s amazing. I’m so glad it all came to be. And good on you for giving it that go!

And speaking of your varied career, is there any track of yours — either band work or solo — that feels overlooked by audiences that you wish had gotten more attention? If so, what is it, and why?

DG: Yeah, actually. I’d probably say “November New,” from the split 12-inch that I just mentioned. It’s kind of been overlooked, mostly because we put that record out ourselves. Jem’s band on one side, and me as da Googie on the other. We paid for it ourselves and had no distribution. We just sold it on tour. It’s sold out now — we pressed 300, and they’re all gone. The only way to hear it now is on Bandcamp or YouTube. And I’m terrible at social media, so barely anyone knows about it. I think like a thousand people have seen it, and maybe 20 people bought it through Bandcamp.

KP: Well, that makes it a little more special though, right?

DG: Yeah, it definitely does make it special. But still, of the three tracks on that record, that one is the one I’m most proud of.

KP: Okay, well, I have homework!

DG: I’ll send you the link.

KP: Please do! I'd love that.

What would you tell your younger self?

DG: I’m not sure there’s much that I would say to my younger self. Honestly, I don’t think I really listened to advice back then. But if I had to say something — and this might sound ironic coming from someone who’s in a band that took 22 years to make a record — I’d say to be patient. Things take time. There’s a tendency when you love a band to assume they sounded like that from the very beginning, but nobody is born a finished product. You have to work at it, and you have to be patient.

That said, I think I’ve always been patient. So maybe if I could give myself advice, I’d say, “When you’re patient, you actually need to be more patient.”

KP: Okay, well that’s actually advice that I really need to hear! I’m not very gifted in the patience department. [Laughs].

DG: Okay, perfect! So you take it then. [Laughs].

KP: What advice would you lend to women about life, work, or love?

DG: Well, the same thing: be patient! [Laughs]. Just be patient. It'll work out in the end — or not, you know?

KP: But either way, you'll live, right?

DG: Exactly!

KP: What do you feel makes a provocative woman?

DG: Someone who challenges themselves as much as other people. A woman who stands her ground.

Photography (in order of appearance): Kevin Cummins, Lindsay Brice, Amy Ridler, Ian Dickson, Avalon