Jennifer Finch on Feminism, Punk, and the Enduring Power of L7

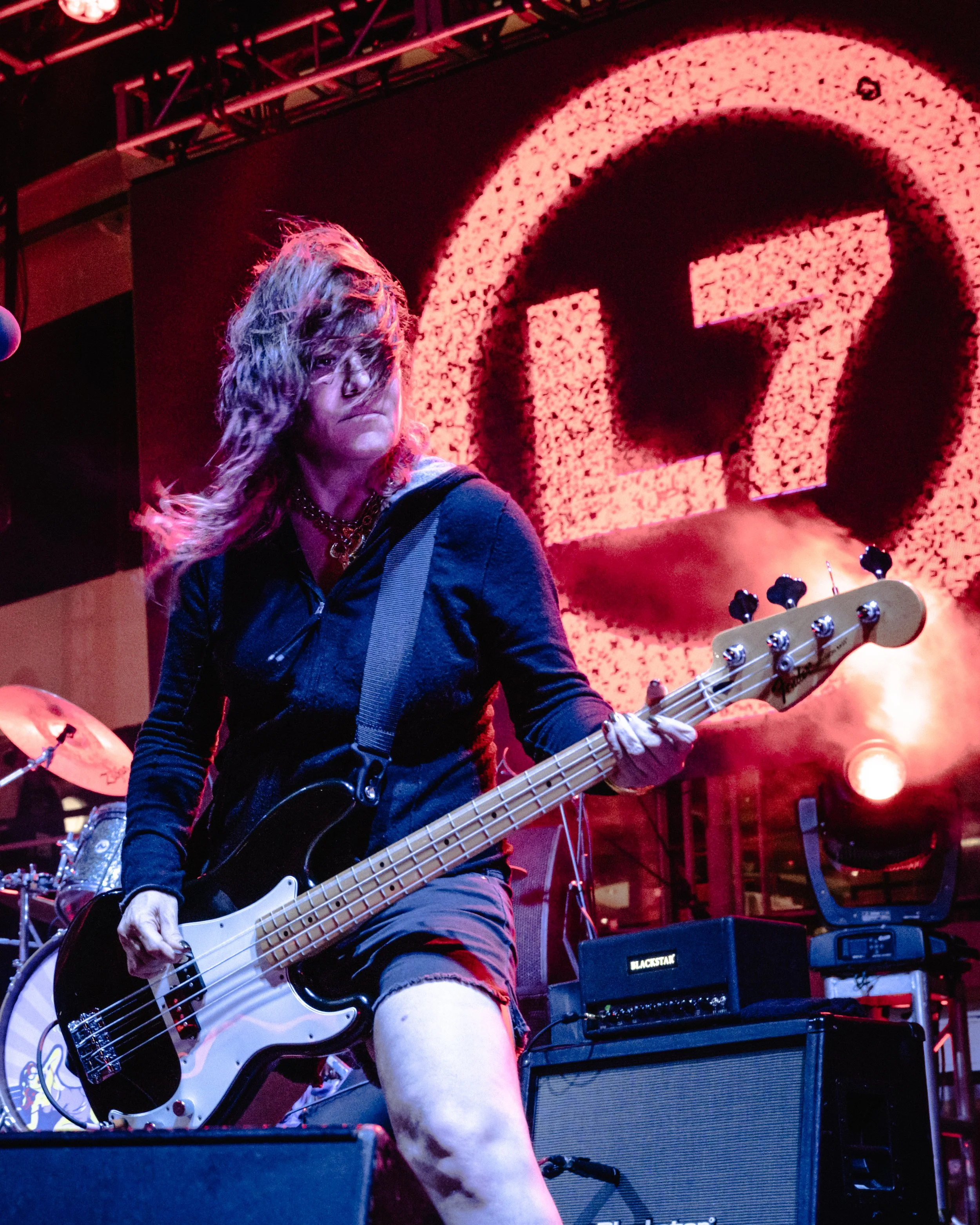

Jennifer Finch is punk rock incarnate — a bassist, vocalist, photographer, and fearless provocateur whose raw energy and uncompromising attitude helped define the sound and spirit of 1990s alternative music.

Emerging from Los Angeles in the mid‑1980s, Finch first played in Sugar Babydoll alongside Courtney Love, Kat Bjelland, and Suzanne Ramsey, before joining L7 in 1986, completing the lineup that would soon become legendary: Suzi Gardner, Donita Sparks, Dee Plakas, and Finch herself on bass. With their abrasive, high‑energy blend of punk, grunge, and metal, L7 carved out a space where women could be aggressive, unapologetic, and hilarious all at once — a stance captured in landmark albums including Smell the Magic (1990) and Bricks Are Heavy (1992), the latter featuring the iconic single “Pretend We’re Dead.”

But beyond the stage, Finch’s influence invaluably resonated through her undeterred activism and strong DIY ethos. L7 co‑founded Rock for Choice in 1991, bringing together musicians, fans, and grassroots networks to raise awareness and funds for reproductive rights, a model of how punk could be both fiercely fun and politically consequential. After leaving L7 in 1996, Finch continued to push creative boundaries with projects including Other Star People and The Shocker, maintaining a career that prioritizes authenticity and personal expression over commercial convention. Her photography of the Los Angeles scene also remains an critical archive of underground culture.

Reuniting with L7 in 2014, Finch helped the band reclaim its position as a vital, uncompromising force in music, touring globally and releasing new material that proves their fire has never dimmed.

Today, Jennifer Finch stands as a touchstone for generations of artists who value courage, independence, and irreverence. She didn’t just play in a band — she helped define what it means to be a woman unafraid to take up space, both on stage and in the world.

KP: Regarding your incredibly legendary career, you said, “I didn’t want to be a musician. I wanted a lifestyle of being a musician. I wanted to do drugs. I wanted the boys. I wanted to travel. The unfortunate part was that I had to learn how to play an instrument.” Looking back now, how did those early motivations shape your path? And at what point did the craft of actually making music become meaningful to you, if you feel that it ever did?

JF: That’s such a good question because I came from an era — part of punk rock and part of art performance — where there wasn’t a lot of internal or external critique of the artists who were working. I didn’t know it at the time, but I think that was a form of rebellion against traditional art paths. I was in it to win it and have fun and meet people. Of course it wasn’t just the boys that I was interested in, but the girls and everybody else involved, as well as being part of something that wasn’t what I grew up with. I grew up in a lower middle-class, working-class neighborhood with people who worked in factories at different levels here in West Los Angeles, which doesn’t really exist now, but it did back then. That was my way out of that lifestyle. I wouldn’t have known any other way. Nobody went to school; everyone had trades or got married and had families. I’m really from that neighborhood — as I’m sure a lot of people my age are — but I wanted to explore a different path.

I started as a photographer. Photography was something needed; it was the glue that held together the scene. I could take pictures, and as I took photos of these live performances — not just musicians and bands, but performance artists, people coming into clubs lighting things on fire… All of that stuff happened in the early ‘80s. I think a lot of that performance came up through the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. By the time I got to it, it was something else, but I didn’t know that — I was still young.

But then, as you said, I had to learn to play. I had always played music and enjoyed it — I played in a band at school.

KP: Oh, did you? What did you play?

JF: At first I played trombone, but then I moved into violin and piano. Honestly, I’m not a great musician. I know great musicians and work with great musicians, but I wouldn’t say that I’m a great musician myself.

KP: That’s really cool. I wish I could play the violin; that was something that I could never do. I was a classically trained pianist from a very young age, and then I transitioned to guitar when I was about six or seven. I couldn’t play the violin well at all because I was used to strumming strings and not bowing them. I tried so hard and it sounded so bad for so long that I had to give it up. [Laughs]

JF: Violin is an interesting instrument. If you can find a reasonably priced one, it just sits on your coffee table or next to your bed, and you only need to practice a few minutes a day. After a year or so, you just get used to it.

KP: Maybe I gave up too soon.

JF: Well, we have a lot to do in life. We all just have a lot to do. [Laughs]

KP: That’s very true. Maybe I’ll have to revisit it.

But similarly — and you’ve already touched on this — but you said that you ran away “for no other reason other than the fact that you wanted some adventure,” and during that time you captured your life — your experiences with drugs, chaos, and freedom — through photography, creating a key archive of underground culture. How do you feel living that way shaped who you became as both a person and a musician?

JF: Yeah. So, I love drugs, and I realized quickly that I wasn’t great at living a prescriptive lifestyle — having to be at school at 8 a.m. every day and leaving at 3. I ran away pretty young, at 13 or 14, then came back around 16 or 17 and returned to traditional high school. During that time, I did a lot of drugs, photographed, hung out with shady people, was shady myself, was part of the punk scene, went to shows — multiple shows a night in Los Angeles.

KP: That’s so amazing that you had that culture. I was born in ‘93, so we had CBGBs here in New York of course — my uncle drummed with the Ramones there for a while — but by the time I was a teenager and could experience things, it was 2011, 2012. We had just passed that garage-era New York scene — the era of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, whom I adore — and were stuck in a weird place. I didn’t have that experience. It must have been really cool, because California back then was teeming with energy.

JF: It definitely was. For me, in Los Angeles, the sun went down, and that was when everything started. It was symbolically kind of a dark cultural era.

You know, I often think about your generation — you had to fight hard for your culture, and I admire that. That’s something to look at. And that’s not to dismiss that you missed something, because you definitely did — and you had to make something because of it.

KP: That’s very true. And especially here in New York, a lot has disintegrated. It’s much more commercial.

“I never had the sense that being in a female body meant that I couldn’t do something. I just did me until I couldn’t anymore.”

JF: It’s definitely commercial. LA and New York are where you go to be commercial now. Younger people probably need to go to Atlanta or Austin or other cities where there’s still scene-making.

KP: On a wider scale, I think the proliferation of social media has also made a lot of things in the scene seem quite performative. People have to sell their souls to an algorithm instead of making music that they genuinely love, something that might not fit into a thirty-second TikTok clip. On top of everything else, I think that makes it a lot tougher, too.

JF: Or that’s the art of it, right? The performative aspect of it is the art. So find what you can and break it.

KP: That’s true. That’s a much more optimistic way of looking at it. [Laughs]

But as I mentioned, you documented your early life through photography. How did you first start working with the camera? What were you trying to capture? And did you know that it would become a historical archive of underground culture?

JF: I really did not know that it would become a historical archive. I was literally just walking around with a camera underage so I could get into clubs. People thought that I was there to do business. It made it easier. I could see the bands that I loved; they assumed that I’d show them photographs at some point. Some rolls of film I never developed; some I developed but never printed because printing was expensive. In 2008 or 2009 — one of those years when capitalism fell — I discovered boxes in my garage of rolls that I had never even seen. I packed them up and sent them out to be scanned. I’m still going through them today, still finding things that I didn’t know I had.

KP: Wow!

JF: I know. And I’m not into books or anything, so it’s difficult. Books are too static. I should have been born in 2000 or something.

KP: We can swap.

JF: Thank you. [Laughs]

KP: In a past interview with John Norris on MTV, you responded to L7 being labeled “a girl group” by saying, “Well, it’s part of us. We are who we are, but there are many parts of us as well.” When you look back now, how do you feel about the way gender shaped people’s perceptions of the band? And how has your relationship to that label evolved?

JF: That’s a very interesting question. L7 just celebrated our 40th anniversary and played a big show in Los Angeles. It’s interesting to reflect on what it means to have been part of a music scene for 40 years, and to have been part of a ’90s scene where we were seeing if we could step into the mainstream — and what that would do to the mainstream gaze. There were only so many roles for women as performers in the mainstream. There were almost five characters you could step into. I still look at pop today and wonder how much has actually changed. You still need to work the underground and the margins to create.

Back in the ’90s, I wasn’t exposed to formal feminist theory or culture theory, the things I love now. I didn’t have the language — and thankfully I didn’t, because no one wanted to hear it. The best answer was, “What are you talking about? Sorry, I’m confused — what do you mean, girl music?” Just push through it and change the language, instead of creating conversation.

KP: That makes sense. Did it matter to you if the person asking that question was a man or a woman?

JF: My opinion and personal experience is that it didn’t matter who did the interview. If it was going to be released commercially on legacy media, then it was not going to have an academic element. It wasn’t going to be instructional. It wasn’t going to be, “Hey, we could have a new world; think about it this way.” I don’t care who did the interview — Gloria Steinem could have done it.

KP: [Laughs] So your reaction would be solely based on the source.

JF: Totally. The source and their audience. Any body of work that I’ve had is about the audience as the creator, and legacy media manipulated the audience into certain preferences. I think the audience should have their own preference. By 1995, I thought, This sucks, I’m exhausted, I need to quit. I had been in L7 since 1986; Suzi and Donita had been doing the band since a year earlier. I was burnt out. There was nowhere to go. We couldn’t return to the underground because what we had built up was no longer there. And there was the rise of Riot Grrrl, which was great, but it was completely manipulated and reformulated by the mainstream, which was sad. That still makes me cry sometimes. So I took a break and came back with Other Star People in The Shocker and did music the way that I wanted to.

“You’re never going to figure it all out. Just go do it. Keep a diary, watch your patterns, and change what’s not working. Surrender to change and know your options — they’re out there, you just don’t know them yet.”

KP: L7 was culturally successful, but do you think your success was limited by gender bias? If you were all men, do you think your cultural or financial success would have been greater?

JF: Definitely, it would have been a very different career and experience. I never had the sense that being in a female body meant that I couldn’t do something. I just did me until I couldn’t anymore. But a couple things hit me hard early in our career. For example, when we were on Epitaph Records — Bad Religion, Offspring, Green Day — we went to see an attorney in Los Angeles to review a contract. After everyone left the room, he asked how old the other girls in the band were. They were maybe 22 or 23, but I felt I needed to lie for the first time. I said that they were 19 or 20, and he said that the record companies would see that as us having at least another record in us. It was gross. We weren’t even on a major yet.

Then when we got on a major, a friend’s dad — who was a radio promo guy — told me that rock radio wouldn’t allow two female vocalists back to back. He said that no matter how much money they threw at stations, they wouldn’t do it. I was shocked. We were already invested, already touring Lollapalooza in ’94. It was disheartening, but I always had hope. I still have hope.

KP: Definitely. And people often say that women are so competitive with each other, but women have been so historically pitted against each other. You couldn’t even have two female bands headline. It’s a construct, not a reflection of women as a whole.

JF: Definitely. If you look at women in music in the ‘90s, you can see how the media pitted them against each other or did articles about “the top three women in music” instead of just including them all. Not much has changed. It’s expanded a bit, but still. I love Chappell Roan, but she still looks like something familiar, even though she says that she’s not. Sabrina Carpenter? People just missed Britney. Miley Cyrus is aging out and probably working harder than she should. It’s interesting to watch.

KP: You were instrumental in Rock for Choice and connected with activist circles like Positive Force DC, using punk as a vehicle for abortion access and reproductive rights. Looking at the present moment — where it very much feels like we’re moving backwards — how do you think punk can still mobilize or protect in this fight? And what role should artists take now?

JF: When I engage with commercial artists — on TikTok or behind the scenes — and they talk about politics or reproductive freedom or the breakdown of the political system, I’m interested in what they’re saying. Everyone is on point, so it’s not about the artists themselves. Rock for Choice wanted to help educate artists to talk about these issues in calm, meaningful ways, to discover their value systems. That was a successful, though unofficial, part of Rock for Choice.

The punk part was to say: look, we might be doing big concerts, but people can have homegrown events in their own communities — spaghetti dinners, poetry readings, performance art, local bands — and bring in political conversations. They could have someone from a local women’s clinic come in and say, “We need volunteers.” Again, the audience mobilizing itself is the punk part.

KP: L7 reunited in 2014, but now we are very much in this wayward world, particularly here in America. Do you feel the same urgency and spirit that fueled you in the ’80s and ’90s? What does performing live mean to you now?

JF: I love it. I’m really having a great time. I love audience performance. I don’t want to think that we’re going backwards; I just think that the structure that was put in place is breaking down. My hope is that over the next two years, smart people will come up who weren’t overly burdened by the 2000s punk scene, and hopefully life hasn’t educated them out of their curiosity. They’ll help build structures that are more long-lasting and educational. That’s my hope.

KP: In my generation, when I came of age in the late 2000s, it felt like there was so much hope — gay marriage was legalized, reproductive rights were secure. And now at 31, watching it all degrade, it feels difficult. I like your hopeful framing better.

JF: At 31, I suppose you’re right on point for thinking that everything is great in your twenties and falling apart in your thirties. But as your 59-year-old older sister: life isn’t good or bad; it’s what serves and what doesn’t serve. Something about that era didn’t serve properly to protect people’s rights, so we have to look at that and build the next thing.

It’s obvious that a hardcore Christian narrative entered the churches and convinced people of things that weren’t even religious. We really need to look at that. I was never raised with religion, so I’m not burdened by the evils that some people were traumatized by. But I do work with women who were traumatized, and they need to alchemize that trauma into something powerful, because the trauma was meant to stifle them and take away their language. They need to find language in it and be motivated to speak, to change the narrative, and remove it. The U.S. is land that people came to because Europe wasn’t religious enough — they came for a more religious, off-grid experience. We’re still living with that.

KP: We definitely are.

To turn back to the band, Shirley Manson once said of L7’s look, “I loved that these girls were dressed like guys but were hot. They were sexy, and I loved that combination.” How did you think about image and presentation? What did you want your visual language to communicate about power, femininity, and punk? Or was it completely organic?

JF: It’s interesting, because I love the fashion world, though I don’t know anything about it. I feel like young people in fashion are doing the most innovative performance work now. People ask what the next punk band is, but it’s not anything you know; it’s happening in other forms.

We didn’t want to signal over-femininity, or at least the media expression of it. Rock was king and the bimbo was queen. There was a certain look that rock women had — I’m not judging, I’m just noting the pressure that women felt to feminize a male counterpart: taking a leather jacket and giving it boobs or lace as if to say, “We’re here, but we’re feminine.” None of that made sense to us.

I was a skater kid from the west side. I was in the pit, went to punk shows, and wore certain clothing because I was doing something physical and dirty. I didn’t wear dresses. I didn’t get into vintage fashion until a bit before L7, and then much later.

As for that clip in particular, I think that Shirley Manson just saw some shots that we just showed up for, you know what I mean? There was no stylist and it was just us rolling out of a van and taking a photo and that's what she saw. We never dressed it up really.

KP: I love that. It made magic.

To continue on from that, L7 were sometimes criticized for your so-called “badass” approach. I saw some critiques online, particularly from Riot Grrls, who felt that you were moving into the industry rather than completely breaking it down, or engaging with feminist tropes in ways that read as imitating masculinity. In response to that, you’ve said, “I just go do my thing” — that you weren’t imitating anyone, you were just being yourself. How did you navigate these critiques, sometimes even from other women, and what did it mean for you to define your own path as a woman in punk on your own terms?

JF: Well, for many years, I had to just explain that I never went to college. [Laughs] I was 18 when I joined this band. The Riot Grrls all met at liberal arts schools, which is amazing and unique — something that people should keep in mind when they think about encouraging their daughters to play guitar. Don’t necessarily send her to music school; the magic of punk is that it’s outside those structures.

When I do tours at the Punk Rock Museum, I look at the threads that hold the scene together. Proto-punk bands like Talking Heads, The B-52s, Ramones, Iggy Pop — all these New York-centric bands that transformed the music industry — were just people trying to express themselves and hoping to be commercially successful. They mostly met at art school — that’s a pattern. There are exceptions, like the Ramones, but generally, these were street hustlers breaking the system in their own way.

I’m even going to stand by that statement for Britain. In the little British section of the museum, I can point to every single one of the bands that are on that wall — and we're talking almost twenty, from The Damned, to the Sex Pistols, to The Slits, who aren't really represented, to Siouxsie and the Banshees, to Adam and the Ants — everybody met at art school.

And to go back to America, Iggy Pop didn’t invent punk alone — I think that Nico invented Iggy Pop. She went to art school, knew hardcore performance art, but her role was largely as a muse to men. Yet she influenced modern punk profoundly. That context is important.

As for Riot Grrrl, we were making records before Bratmobile and Bikini Kill. Their philosophies were incredible — they created their own economy, running labels, press, photography, everything for themselves. People reduce it to just being “feminine” or “disrupting stereotypes,” but they were really building infrastructure outside of commercial music. That’s what I admire.

KP: You’ve also talked about feminism as dismantling old power structures and exposing them. Early in L7’s career, you faced both subtle and overt abuses of power — from offhand comments about your age to manipulation by people in the scene. How did those experiences shape your understanding of power and agency in music, and how do they influence how you operate today

JF: Thank you for asking that. I grew up in Los Angeles, which felt like a final frontier of freedom. Sure, it’s considered vapid or industry-focused, but it was also a place where being weird was okay. People were taking risks to be commercially viable, whether entering the music industry or carving their own paths in life.

I’ve lived in my own bubble, my own algorithm of what’s normal, where it never felt weird that I didn’t have kids in my 30s or 40s. That shaped me. I’ve realized that the music industry is just another structural power — it’s about systems, not individuals. Independent labels — Fat Wreck Records, Go-Kart, Epitaph — they’re microcosms of that same structure. Understanding power as systemic rather than personal helped me navigate my career and my agency in the scene.

KP: On a lighter note, I can’t help but ask this question. [Laughs] During L7’s live performance in France of “Questioning My Sanity,” you famously flung your bass off the stage into the sand many, many, many feet away. So what happened to it? [Laughs] Were you able to use it again?

JF: [Laughs] Oh, that’s a long story. I had always watched male musicians destroy their instruments and was a bit jealous. I’m strong, so I picked up the challenge.

KP: Honestly, you really must be to throw that as far as you did. People don’t realize how heavy solid bodies are!

“It’s obvious that a hardcore Christian narrative entered the churches and convinced people of things that weren’t even religious. We really need to look at that.”

JF: They’re heavy. The bass, called The Ghost, is a Fender hybrid from the ‘80s. I tried to break it during the song, but nothing broke — nothing would fucking break — so I threw into the ocean, started dancing, and never really knew what happened to it.

The next show, our bass tech — who was a really good friend of the band — had recovered it from the beach and said that it somehow still worked. I played it for seven more years, then put it away when I left L7 in 1996. In 2014, during the documentary reunion, I pulled it out again. Now it lives at the Punk Rock Museum jam room. Anyone can go play it. It’s survived decades of chaos and still rocks.

KP: What?! No way. Okay, I thought this question might be pure vapidity, but I’m so happy that I asked it now! [Laughs]

JF: Oh yeah, it’s there! [Laughs]

KP: Turning to the present, are there any artists today who you feel are carrying forward the L7 spirit or approach?

JF: Lots of artists are carrying it forward — but it’s not L7 spirit, it’s your spirit. I encourage everyone to find it on their own.

KP: Looking back at your earliest years in the band, what advice would you give your younger self?

JF: I did a lot right, honestly. I was a monstrous drug addict from 14 to 24, and I love heroin — it’s hard to talk about — but I got clean. But when I got clean when I was 24, I used to tell myself, I can do heroin at any point I want to, but the really great thing is that I don't have to today. But I can tomorrow. Like first thing tomorrow, I can go do it. And now I can’t. I don't. You know, I live in an area where people are nodding on the streets — I see them getting loaded, but it's fentanyl. It's other versions of what it used to be. And I'm like, Oh, if I could have, I should have just saved some my heroin and hid it in a vault somewhere. And then when I'm 90, I could have done it. [Laughs]

I really did the best I could to prioritize my mental health. I recognized the difference between all of these drama queens… I was around so many drama queens, I mean, I was friends with Courtney Love since we were 16.

KP: [Laughs]

JF: And, about that, on a serious note, I was around when her husband fucking killed himself and attempted multiple times before that. Honestly, a lot of folks didn't make it through the ‘90s. But I did, and it was because I prioritized my health. I started seeing a doctor with annual checkups from a pretty young age. I really turned things around and tried to value my life. I bought a house at 30.

KP: Wow!

JF: I know. It sounds wild, but I always tried to see where things were going and make choices accordingly.

But I think that I would tell my younger self to not fucking worry so much and to step into the spotlight, because I had a lot of self-esteem issues. I didn't want to be a central focus. It was only later in life with Other Star People that I bleached my hair platinum blonde, got on a major label, and made soundtracks to movies like Scooby Doo and Office Space. I really stepped into that role, and it was pretty fun.

The Shocker was the same — I had creative partners and people that I worked with, but I was definitely experimenting with breaking down gender roles for women. I wanted to do things a little bit weirder and a little bit different. I’m very fortunate that I got to do that with both of those bands.

KP: And you killed it.

What general advice would you give women about life, work, or love?

JF: You’re never going to figure it all out. Just go do it. Keep a diary, watch your patterns, and change what’s not working. Surrender to change and know your options — they’re out there, you just don’t know them yet.

KP: And, finally, what do you feel makes a provocative woman?

JF: A woman who walks how she speaks. She critiques something, and she acts. Risk-takers — the ones who challenge structures and expectations — are the most admirable. Commercial success isn’t the measure — it’s about authenticity and knowing yourself. My stage persona with L7 is my cartoon — that's my red-headed, go crazy on stage, throw a bass alter ego. And then there's who I am. And I think knowing that is provocative.

Photography (in order of appearance): Jesse Fischer, Karla Moheno, Gie Knaeps, Karla Moheno

Hero image: hair by Aimee Mrquardt, makeup by Roxxi Dott, location by Shaun Kumma